Lisa Alther is a Vermont novelist who has made a lot of money writing books that rely heavily upon lesbian sex. In 2012, she “caught the wave” in the wake of the Kevin Costner TV show by writing a book on the Hatfields and McCoys. In its review, the Wall Street Journal called Alther “An expert on the feud.”

There is not a single sentence in that book that is both new and true. She tells us that she parsed the prior books and chose the tales she liked for her book. It is obvious that she never laid eyes on a single original document in a courthouse or archive. Ms. Alther entitles the introduction to her book, “Murderland.” That title is a good indication of the validity of the tale that follows.

Lisa Alther said of Truda McCoy: “she wrote an account that reads like a novel — and is probably about as reliable as one.” After stating early on that Truda McCoy’s book is “probably about as reliable as a novel,” what does the novelist, Alther do? Why, she cites that “unreliable” source one hundred and two times in her footnotes!

With one hundred and two citations of Truda McCoy in one hundred forty-seven pages of feud-related text, it is clear that this author can’t write two pages without falling back upon a book she says is no more trustworthy on historical fact than a novel. And she touts her book as non-fiction!

The part of Truda McCoy’s book that reads most like a novel is the first chapter, which describes the death of Asa Harmon McCoy. A comparison of Truda’s original manuscript, which is in the Leonard Roberts papers at Berea College, it is obvious thatthis chapter in Truda’s book is largely the work of Leonard Roberts.

Alther’s first chapter is also on Asa Harmon.

Truda McCoy, who did not claim to be writing a history, used her imagination to tell the story of Harmon McCoy’s death the way she envisioned it. Since no one knows the details, McCoy does no great violence to historical fact by telling the story the way she imagines it might have happened. Knowing what it represents, this chapter is actually the best part of McCoy’s book. Although one can get a real feel for the situation in January, 1965 by reading McCoy’s chapter, no serious scholar would mistake it for real history.

It is a far different thing for a later writer to use it as if it was real history, but that is what Lisa Alther did, in a near-verbatim regurgitation of McCoy’s first chapter. Alther said Truda McCoy’s book read like a novel, and that is true of most books by descendants. Alther’s 2012 book, Blood Feud, reads even more like a novel than does the one by Truda McCoy. In fact, in her fictional chapter on Asa Harmon, she follows Truda McCoy so closely that one has to look at the title to know which book one is reading.

Here are two examples among many sentences that are so similar that it is hard to distinguish Alther from McCoy:

TM: “Pete and Patty started toward the cave. They had not gone far after they reached the woods, until other tracks joined the tracks that Pete had made on his previous journey to the cave.”

LA: “they reached a junction at which new boot prints emerged from the woods to join Pete’s tracks up the hill toward the cave.”

TM: Then, “Halfway to the cave, they found Harmon lying across a snow covered log. The snow around him was red with his blood.”

LA: “Alongside the trail, just below the cave, they spotted a fallen oak tree. Across its trunk sprawled Harmon McCoy. The snow on the ground around him was stained scarlet.”

Alther takes McCoy’s harmless fiction and transforms it into “history,” without even giving McCoy credit for her words. This narrative exists nowhere else in feud literature, except with Truda McCoy and Lisa Alther. Knowing what it represents, this chapter is actually the worst part of Alther’s book.

Alther had a few new ‘facts’ in her book, but they are all egregiously false.

One of her “New” discoveries is where she wrote, (p. 35) of Ran’l McCoy: “he charged Devil Anse Hatfield with stealing a horse from his farm in 1864.” On the next page, she writes: “Ranel McCoy and Devil Anse Hatfield filed several similar suits against each other in the years following.”

This is not a minor human error that any writer might make. It is a whole cloth fabrication of something that is of central importance to her tale. And it is absolutely false in its entirety.

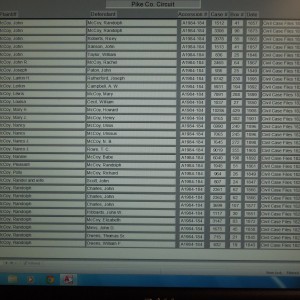

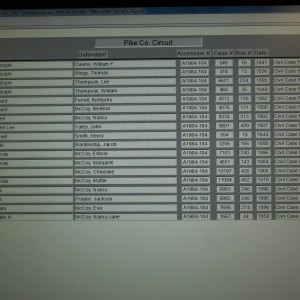

As you can see in this Index, Randolph McCoy filed several lawsuits, NONE of which had any Hatifeld–much less Devil Anse–as a defendant.

Randolph Mccoy cases continue on the next page. He was actually quite litigious. Ran’l was involved in many suits contesting the value of hundreds of pigs, but no one knows about them.

There are NO lawsuits in the record where Randolph McCoy sued ANY Hatfield, much less Devil Anse Hatfield. The index also shows that Devil Anse never sued ANY McCoy, much less Ran’l McCoy.

Lisa Alther, whose previous novels dealt a lot with sex, has much more sex in her fictional “history” than any other feud writer. Everyone knows sex sells in 21st century America– and the kinkier the better. Alther mentions at least three times that Ran’l McCoy’s cousin, Pleasant, was accused of copulating with a cow.

When describing the widely publicized photo of Ellison Hatfield in his Civil War uniform with his revolver in front of him, she says he is “fondling his pistol.”

In her chapter entitled The Corsica of America, Alther says: “If only the feudists had spent as much money and effort on acquiring contraception (which was, in fact, available in other regions of the United States at this time) as they did on acquiring guns, ammunition and moonshine, a different scenario might have evolved.”

I must admit that the scenario would have been quite different if someone had sold condoms to the feudists. When Devil Anse went to federal court in 1889 on a moonshining charge, he faced the standard year-and-a-day if convicted. Had he been peddling condoms, however, he would have faced up to five years in the pokey and a two thousand dollar fine plus court costs.

The Comstock Act became law in 1870. That law read, in part: “…whoever shall sell…or shall offer to sell, or to lend, or to give away… any drug or medicine, or any article whatever, for the prevention of conception, or for causing unlawful abortion, or shall advertise the same for sale… shall be imprisoned at hard labor in the penitentiary for not less than six months nor more than five years for each offense, or fined not less than one hundred dollars nor more than two thousand dollars, with costs of court.”

Whether this declared expert is ignorant of history or simply chose to condemn several generations of Appalachians while knowing her statement was untrue, I know not. The Comstock Law remained in full force against contraceptives until 1936. The 1936 decision applied only to married couples. The right to contraception for unmarried persons was not recognized until 1972.

We learn more about the mind of the novelist who penned this screed when she says she was driving through the Cumberlands and saw a billboard advertising an indoor firing range. Alther says: “At the top stood a large cutout of a pistol, pointed upward at an angle. The barrel resembled an erect phallus, the trigger guard outlining a testicle.” Now we know why she thinks Ellison Hatfield was ‘fondling’ his pistol in his Civil War photo. To some people everything is about sex, and those folks write a lot of books — and buy a lot of books.

The Wall Street Journal calls Alther “An expert on the feud.” I place her in the top tier of the folks I lovingly refer to as “The feud liars.“