The N&W Railroad’s Annual Report for 1886, published in early 1887, was the most important single document in understanding the second phase of the Hatfield and McCoy feud, which occurred in December 1887 and January 1888. The railroad management stated on page 24 of that report that they were going to build a railroad connecting Virginia with Ohio

As the Tug Valley was probably the preferred route to connect Virginia with the Ohio River, land in Tug Valley which was, as stated in the N&W Report, “entirely without transportation facilities,” suddenly came into the sights of outside money interests.

Financial moguls from outside the hills did not mount up and ride into Tug Valley and approach the locals directly. The appearance of a well-groomed man at the door, saying, “Hello, I am Sam Clay, from Lexington, Kentucky, and I am here to buy your land,” would have aroused a defensive reaction in even the most gullible mountaineer.

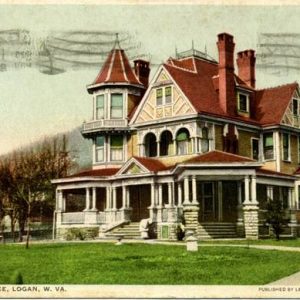

So, the moguls used local people to buy the land from their kin and neighbors and then flip the title to the real buyers. In Logan County, the locals who bought the land and then flipped it to the moguls were mainly Nighbert, Sargeant and Buskirk. U.B. Buskirk built this humble abode in Logan on money he made by buying and then flipping the land of his Logan County neighbors.

In Pike County, Colonel John Dils stood head and shoulders above everyone else in the amount of land bought and sold. For a quarter of a century Colonel Dils bought land from the county on land warrants, while being on the bonds of almost every man who held county office during that time. The Colonel was the foster father of both Bad Frank Phillips and lawyer, Perry A. Cline. Dils also sat in on the ‘confession’ of Ellison mounts.

The local magnates, who lived in the county seats, could not always approach the land owner themselves. To a landowner on Tug River, a “money man” from Logan or Pikeville was an outsider. So the county seat moguls used someone closer to home.

At the time that report was issued by the N&W, men who had been indicted in Pike County five years earlier for the murder of the three McCoy brothers owned thousands of acres of land smack dab in the heart of the “Billon dollar coal field,” and on the most likely route of the coming railroad. Therein lies the real reason for the invasions of Logan County by the Frank Phillips gang in December, 1887 and January, 1888. Of course the reader can accept the alternate explanation, which is that the Pike County ruling clique was suddenly stricken with a case of law and order enthusiasm, but I believe my analysis makes far more sense.

When Simon Bolivar Buckner assumed the Governor’s seat in Kentucky in September, 1887, he was faced with raging feuds in several Eastern Kentucky counties. Nothing had happened in Pike County since four men were killed in three days more than five years earlier. The Louisville Courier-Journal, whose editor, Henry Watterson, was conducting a virtual crusade against mountain feuding, carried dozens of articles about the feuds in the years between 1882 and 1887. The Courier-Journal ran two short paragraphs in August, 1882 about the trouble at the Election in Pike County, but not another word until January, 1888.

As Buckner campaigned that summer, there was a battle in the main street in Morehead, county seat of Rowan County. The battle featured more than sixty feudists, with four men killed and several more wounded.

The concurrent feud in Perry County also featured a battle in the county seat, wherein the courthouse and jail were both riddled with bullets, as the opposing sides took up positions in the county buildings. These feuds featured the county elites, businessmen and county officials in active roles. A circuit judge, county sheriff and several lesser officers were slain.

Upon taking the oath, Buckner proceeded almost immediately to–not send the militia to pacify Rowan or Perry County–but to increase rewards on men who had been living peacefully for more than five years in Tug Valley. The only thing that could have caused such behavior on the part of the new governor was pure political power; the kind of political power that comes from money.

The feud books attribute that power to Perry Cline, but that is absurd. A deputy jailer, who served one term as sheriff and one term in the legislature, did not have the power to move a governor to such extreme actions. Colonel Dils, the richest man in Pike County, and the patron of all the county officers might have—but I doubt it.

That kind of power likely came from outside Pike County, and I think I know where it came from. Of course no one can know what transpired behind closed doors with businessmen and politicians a century and a quarter ago, but we can look at what we know happened and use our best reasoning to figure out what is unknown.

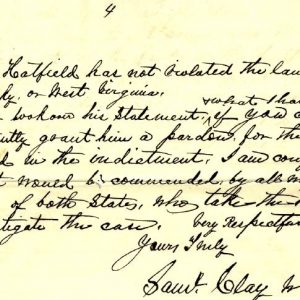

The most important thing that we know happened, because it is in Simon Buckner’s papers, is that one of the richest men in Kentucky, Samuel Clay, Jr., of Lexington, wrote a letter to Governor Buckner in May of 1888, requesting a pardon for Elias Hatfield. Why in the wide, wide world of sports would one of the richest of all the Bluegrass bluebloods be imploring the Governor of Kentucky to pardon a “nobody” from West Virginia? Here is the last paragraph of Mr. Clay’s letter.

(click to enlarge)

More in the next post.