In the politically correct 21st century, there is only one demographic group which can be safely ridiculed on network television; Southern Appalachians. The stereotype of the ignorant and barbaric hillbilly remains as strong today as it was when the yellow journalists of the late 19th century first presented it in the big-city newspapers of that day. The foundation stone of that stereotype is the tale of the Hatfield and McCoy Feud.

Having been born and raised on Blackberry Creek, in Pike County, Kentucky, where the most important feud events transpired, I am personally acquainted with that stereotype. I came face-to-face with it during my first week as a graduate student at Cornell University, in upstate New York. A fellow student from New York City asked me in the grad student’s lounge: “What kind of people kill a hundred of each other over a pig?”

With half a dozen of my fellow students listening to the query, I was shocked and deeply embarrassed. “What the hell are you talking about? I asked.

He then produced a print-out of the microfilm of the New York Times article from 1930, reporting the death of Cap Hatfield. That article said that the feud started over a pig, lasted for half a century and claimed over a hundred lives. I told him it was a crock, and left the room.

I did not stay to argue the point, simply because I knew that my fellow students would not take the word of someone who spoke a dialect that they associated with Southern ignorance over that of the nations “Newspaper of record.” After all, they frequently cited the “Times” as a fact source in their written essays and dissertations.

The feud story existed in two forms when I was growing up on Blackberry Creek in the 1940’s and 1950’s. The version given by the folks who were old enough to remember the events of the 1880’s had a brief story, which began with the Election Day, 1882 killing of Ellison Hatfield and the lynching of his killers two days later. They then spoke of the invasions of West Virginia by the Pike County gang under Frank Phillips in December, 1887 and January, 1888. In this period, they told of the raid on the McCoy home when two more of Ran’l McCoy’s children were killed, and of the killing of two men by the Phillips gang in Logan County, in January, 1888. Their story ended, as the feud books end, with the hanging of Ellison Mounts in February, 1890.

The story given by those born after 1890 was much bigger, and different in many respects. People of my parents’ generation (they were born in 1912) were hugely influenced by the feud books which had been written since the ending of “the feud.” Their feud story had many events and characters which did not exist in the story told by the old folks who were alive when it happened. Many of that later generation had read one or more of the feud books, and all of them had talked to people who had read the books.

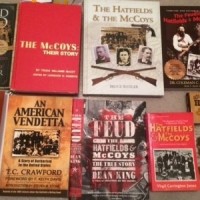

All the feud books, except for my books, derive from the original telling of the story by the New York reporter John Spears. His little book, nine pages in the magazine Current Literature when it appeared in the fall of 1888, is still the basic story. Dean King’s 2013 opus, “The Feud: The True Story,” cites Spears sixty-six times.

The feud story is largely fable, folklore and fiction. Some writers repeat it out of ignorance, simply because they never did any actual research into the historical records, and are not aware of the historical evidence adduced in my three books. Others know what the real history is, but they repeat the yarn from Spears—usually embellished with some fiction of their own creation. Those writers, who actually know that they are writing fiction as history, are FEUD LIARS.

Every writer who repeats the feud yarn and has either read my books, or has perused my Facebook page, https://www.facebook.com/HatfieldMcCoyTruth/ or Ryan Hardesty’s Facebook group, “The Real Hatfield, Real McCoy, Real Matewan” Facebook page, is, ipso facto, a feud liar! https://www.facebook.com/groups/hatfieldmmcoy/

In the current (Spring, 2016) issue of Goldenseal, a magazine published by the State of West Virginia, Keith Davis writes: “John R. Spears wrote one of the early—and highly inaccurate—accounts of the feud. (p. 16) Davis is, of course, correct. Spears’s account of “The feud” IS highly inaccurate, but Spears is not on my list of “Feud liars.” The next installment will explain why Spears did not make that dishonorable list.