Most writers of books on the history of the Tug Valley in the late 19th century are either ignorant or dishonest. They have a problem spinning a long, convoluted yarn of decades-long inter-family violence when the fact is that all the violent events that either wounded or killed anyone occurred on just THREE days!

On August 7, 1882, three McCoys butchered Ellison Hatfield. On August 9th, 1882, The Hatfields lynched the three McCoys. On January 1, 1888, the Hatfields burned the McCoy home and killed two McCoys. How do I know that this is all of it? First, I talked to more than a dozen people while I was growing up on Blackberry Creek who remembered the 1880’s, several of whom were present at the 1882 election. Those three days were all the feud story that they had.

Secondly, about 2000 hours of research in the documentary record have convinced me that those old folks were right. The best evidence is the sworn testimony of Jim McCoy, eldest son of Ran’l, in the 1899 trial of Johnse Hatfield for the murder of his sister, Alifair, during the New Year’s raid. So intent was Jim McCoy upon hanging Johnse that he testified first for the prosecution and was then allowed to sit at the prosecutor’s table and feed them question during the trial.

After raising his right hand, Jim was asked when the trouble between the two families started. Jim answered, “It STARTED at the 1882 election.” Then asked what happened between August 1882 and the 1888 New Year’s raid, Jim testified: “We tried to get them arrested, but WE never HAD any TROUBLE.”

With only three days of violence, separated by more than five years, how does a writer come up with dozens of feud events, stretching over decades? The answer is simple; they make it up!

Dean King, who wrote the biggest yarn of all, says that he did four years of intensive research. So, after all that digging, how does he come up with a quarter century feud that claimed a dozen and a half lives? Well, he simply MADE IT UP!

Let’s look at one of the many ‘feud events’ King made up to go back beyond where Jim McCoy said it started. King re-spins the old “Romeo and Juliet” yarn about Johnse Hatfield and Roseanna McCoy, saying, “On this particular election day in the spring of 1880, a number of Hatfields crossed the Tug…”

King says that Roseanna and Johnse first met there and then we have the elopement, Roseanna’s stay at the Hatfield home, Roseann returning to Kentucky, and having a baby that died. Then, a year after that made-up election, Johnse marries Roseanna’s cousin, Nancy.

There was NO election in Pike County in the spring of 1880. There were NO spring elections in Kentucky until after the new Constitution was adopted in 1892. In years that featured only local offices, Kentucky elections before 1892 were held in August, as when Ellison was killed. In Presidential years, Kentucky held its election in November, along with the rest of the country.

But King could not have an election in November 1880, And then have all the excitement he has included in the time between the election and Johnse’s marriage to Nancy McCoy the next May, so he simply backed it up six months and gave us an election that NEVER happened.

Now we will examine one of the many made-up lies King told in order to have a continuous feud during the years when Jim McCoy swore under oath that they “never had ANY trouble.”

King writes: “On a hot summer night, at a dance in Pike County, a mail carrier named Fred Wolford called Jeff McCoy a liar…Jeff pulled out a pistol and shot him dead.”

King has a knack for detail, which causes people like the book reviewers for big city newspapers to laud him for his “detailed research.” After all, how deep do you have to dig to come up with a detail as insignificant as the fact that Fred Wolford was a mail carrier? Mighty deep, I’d say, since there was no such thing as a mail carrier outside of a large city in 1886. The first delivery of mail to a rural address was in 1896. https://psmag.com/economics/a-short-history-of-mail-delivery-52444

This one of more than a dozen lies in King’s book that can be refuted by simply consulting the US Census. The Census says Fred Wolford was a farmer.

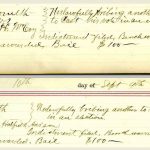

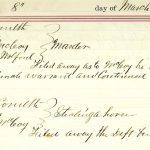

(Click the thumbnails to expand photos.)

Fred died on March 26, 1886, at which time Peter Creek was far more likely to have had a foot of snow than a “hot night.”

From King’s yarn, the reader would believe that the two men met at a dance, and, both likkered up, got into an argument wherein Fred called Jeff a liar and Jeff responded by plugging Fred with his Colt. In fact, Fred Wolford’s death was the result of a Wolford family argument. Jeff McCoy was married to Sarah Wolford, niece of Fred Wolford. Sarah had a brother named Andrew. The court records show that both Jeff McCoy and Andrew Wolford were charged with the murder of Fred Wolford.

According to Fred Wolford’s descendants that I heard the family story from some 50 years ago, Fred was STABBED, not shot. A stabbing makes more sense in a case where TWO men were indicted for the killing. It doesn’t take two to shoot a man.

After killing Uncle Fred, Jeff stole a horse and went on the lam.

Where did he go? To the West Virginia home of Johnse HATFIELD, of course! With a vicious feud between the Hatfields and McCoys going on, according to King, Jeff McCoy took refuge in the home of Johnse Hatfield, with Cap Hatfield as his next-door neighbor! Note that the March 1887 filing says that the defendant is dead.

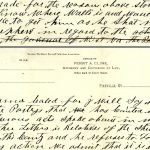

Jeff was indeed dead, having been shot on the banks of the Tug in November of 1886. King writes that after swimming the forty feet of the Tug (it’s actually about three times that wide there) “Jeff, a man of the mountains, clung to the earth. Timing the shots, he suddenly sprang, clawing his way up the bank. Cap nailed him halfway up the slope.” That is false. Cap did NOT kill Jeff McCoy—Tom Wallace did– but King needed it to be a Hatfield killing a McCoy, because, after all, he was writing a tale about a feud between the two families. Let’s look at the very best evidence, which comes from Jeff McCoy’s uncle, Perry Cline.

In a letter to the Governor some two years later, seeking a requisition from the governor for the arrest and extradition of Tom Wallace, Cline told the governor that he wanted very much to get Wallace (spelled Walls),because “He shot my nephew.”

Despite his promise in his Author’s Note to “deflate the legends, to check the biases, and to add or restore accurate historical detail,” King has dozens of flat-out lies in the book which can be proven false BY THE RECORDS.” That’s why King ignores my challenge to a debate, even though I have offered to pay for the hall.