In the biggest and most fictional ‘history’ of the Hatfields and McCoys, written by Dean King, William Anderson Hatfield was first called “Devil Anse” by his mother in 1854, when Anderson was 15 years old. King writes: “Nancy declared her boy not afeared of no kind of varmint nor of the devil hisself. She called him Devil Anse after that. The nickname would prove apt to friend and foe” (p. 20)

In fact, Anderson Hatfield was never called “Devil Anse” by anyone before 1888, when he was so identified the New York reporter T. C. Crawford. Anolther New York reporter, John Spears wrote in the same year. Getting his information first-hand from Ran’l McCoy and Perry Cline, Spears called him “Bad Anse.” Surely Spears would have used the much more sensational “Devil Anse” if any of the Pikeville cabal had known of its usage.

1888 and 1889 featured many articles about the Hatfields and McCoys, with the moniker “Devil Anse appearing only in reports written hundreds of miles from Tug Valley.

Anse Hatfield was sued by several people in the years immediately following the Civil War, and was indicted in Pike County for murder alleged to have been committed during the War. In all cases, he is simply “Anderson Hatfield.”

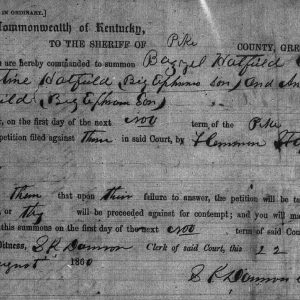

In 1860, Anse was charged with assault along with his brother and several of his Kentucky Hatfield cousins. As one of the other Hatfields was also named Anderson, the court had to distinguish them in the indictment. If he was known as Devil Anse, surely the court would have used that nickname to distinguish him from Preacher Anse. But they named him in the court papers as “Big Ephraim’s son.” Here is one of the court records.

(Click on graphics to enlarge)

There is only one actual written transcript of a criminal trial that featured testimony by major feud characters, the 1899 trial of Anse’s son, Elias for the July 3, 1899 killing of Doc Ellis. The sons of Anse had killed at least four men in the three years prior, and the local authorities had it up to here with their antics. The transcript makes it clear that Anse had about run out his string in Mingo County. When the doctor examined the fresh corpse of Doc Ellis, minutes after Elias shot him, he found a petition in Doc’s breast pocket. It contained the names of many of Anse’s neighbors and demanded the immediate arrest and extradition of two of Anse’s sons.

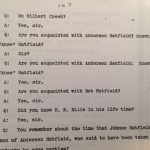

So intent were the local elites upon hanging Elias that they hired the most famous trial lawyer in West Virginia, H.K. Shumate to lead the prosecution. Here is a snapshot of part of the transcript.

Does anyone really believe that the wily barrister, Shumate, would not have used “Devil Anse” if he thought any juror would recognize the moniker?

The first recorded usage of the nickname in the Tug valley came in a 1912 civil case, wherein Anse was suing the Mason Coal company. The company’s lawyer asked him if he was the man sometimes called “Devil Anse,” to which Anse answered in the affirmative.

I grew up among dozens of people whose lives overlapped that of Anse Hatfield, and who were related to him. Three of my eight great, great grandfathers were Hatfields, cousins to Anse. None of the old Hatfields on Blackberry Creek, many of them who were in their forties or fifties when Anse died, ever called him “Devil Anse.” To distingujish him from my great, great grandfather, Preacher Anse, they all called him “Eph’s Anse.”

Anderson Hatrfield (Eph’s son) lived 56 years after the end of the Civil War. He was engaged in violence on only THREE DAYS of that long stretch of time. He led a gang that freed his son, Johnse, from arrest by Tolbert McCoy in October, 1880. He led a group that took custody of the three McCoy brothers from the Kentucky Hatfields on August 8, 1882, and he led the lynch mob that killed them the following day. Real violence by Anse Hatfield occurred on ONLY one day, August 9, 1882.

He lived another 39 year after that lynching and was never accused–not even in the feud yarns–of harming another person.

So, the answer to the title question is that, in 1900, Devil Anse did not exist anywhere except in the scribblings of yarn-spinners, writing hundreds of miles from Tug Valley.

There is no record of Anse’s mother ever referring the man as Devil Anse. This is one of many dozens of places where Dean King failed in his commitment in his Author’s Note to correct the historical record.