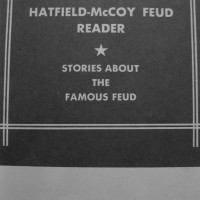

Shirley Donnelly: Baptist Preacher and “Feud Historian”

Clarence Shirley Donnelly was a Baptist preacher for sixty-three years, and a newspaper reporter for about half that long. Whether either of those vocations supports his credibility as a feud historian is up to the reader to decide. He officiated at over two thousand funerals and over a thousand weddings. He also wrote about twenty little books, most of them on religious subjects. And, for some unfathomable reason, he preferred to be known by his middle name.

Donnelly visited Blackberry Creek in the dead of winter to “research” the Hatfield and McCoy feud. I saw a West Virginia car at my Uncle Ransom Hatfield’s house in Februrary, 1955, when I delivered his paper. When I inquired of Ransom the next day about his visitor, he got a big laugh out of telling me that he had been talking to “a man named Shirley.”

Donnelly referred to Ransom as a “kind old gentleman,” but he wrongly gives Ransom’s age at 72, when he was actually 74 at that time. I would have known that he talked to Ransom Hatfield even had I not seen his car there, because he has the three Election Day, 1882 quotes that Ransom passed on from his father, Preacher Anse Hatfield to every writer who visited him.

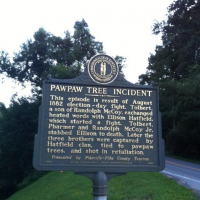

The first is what Preacher Anse said to Tolbert McCoy when the preacher intervened to stop the early fight between Tolbert McCoy and the preacher’s brother, “Bad” Elias Hatfield: “Tolb, Election Day is no day for a settlement.”[1]

The other two appear later in the book, and are the words of Tolbert McCoy to Ellison Hatfield as their fight was about to begin: “ I’m Hell on earth,” and Ellison’s retort: “You’re a damn shit-hog.”

The strait-laced Southern Baptist preacher, Donnelly, renders the last part of the latter as: “a d-n (dirty-word) hog.” This contrasts sharply with the old Harshell, Preacher Anse, who probably never used the six-letter two-syllable word “manure,” when a single syllable would do just fine.

Of course there were other differences between the two preachers. Preacher Anse fought vigorously against the Ku Klux Klan in the 1870’s, while Shirley Donnelly had the West Virginia Grand Cyclops as his adult Sunday School teacher in the 1940’s.[2]

Had Ransom Hatfield been alive in 1971, when Donnelly’s book came out, he would have been greatly displeased at Donnelly’s inclusion of several of the old feud fables that Uncle Ransom detested. Of course one would know very early in the book that the tall tales were coming, as Donnelly says in his Foreword: “Always I would read everything about the famous feud that I could get my hands on, to say nothing of listening to stories of it as narrated by others.”[3]

Donnelly is telling his readers that he is familiar with the prior writings on the feud, from the 1888 newspaper articles through the 1948 book by Virgil Jones. In a little book of forty-five pages, about half of which is not actually about the feud, Donnelly works in most of the fables found in the literature. Thankfully, Truda McCoy’s book did not appear until five years later, so Donnelly did not have busy Belle Beaver, the hillbilly whore from Happy Hollow.

You get an idea of where Reverend Donnelly is coming from when you see what he wrote when he described the aftermath of the events surrounding Election Day, 1882. He says: “From that moment on it was always open season for killing when a McCoy met a Hatfield. During the next 20 years, life was a rough matter along the Tug.”[4]

Considering the fact that Donnelly knew that during the entire twenty years he referenced, not a single Hatfield was killed by a McCoy, that was a pretty big stretch, even for a Baptist preacher. The McCoy descendants should have sued him for libel for accusing them of such gross ineptitude.

This preacher’s penchant for exaggeration is evident when he gives us his feud death toll. While the butcher’s bill can be inflated to a dozen by including the war time death of Asa Harmon McCoy, the killing of Bill Staton by his McCoy cousins, Jeff McCoy’s death which resulted from a domestic quarrel, the killing of Jim Vance and Bill Dempsey by Frank Phillips and the hanging of Ellison Mounts, Reverend Donnelly rounds it off to an even three dozen.[5]

Donnelly says: “There were miscellaneous killings of individual clansmen in lone encounters during the 1880-90 decade when the Hatfield-McCoy feud was raging.”[6] Unfortunately, Reverend Donnelly sees fit to inform us only of the killing of Jeff McCoy among his purported “miscellaneous individual clansmen” slain during the 1880’s.

It is amazing that writings such as Donnelly’s are cited by people who purport to be writing history. When Donnelly gives his recitation of the farcical “ambush of the innocents,” wherein the Hatfields in some unknown manner discover that Ran’l and Calvin will be going to Pikeville, and set up a roadside ambush, he says: “As I recall the story, both horses of the Scotts were killed and one of the riders badly wounded by the ambushers.”[7] (italics mine)

A “story” which Donnelly vaguely recalls and attributes to no one, is repeated as history by Lisa Alther in 2012 and by Dean King in 2013, and prestigious press organs laud them as historians and feud experts. Beam me up!

The vaunted Hatfield marksmanship is absent during the years between the lynching of the three McCoys and the killing of Jeff McCoy more than four years later. In the several engagements alluded to by Donnelly during this period, all the Hatfields accomplished with their Winchesters was one innocent man wounded. The Hatfields did much better with cow’s tails, with which they are said by Donnelly to have killed at least one woman.

In agreement with most other writers of feud fables, Donnelly would have us believe that an ambush party of several Hatfields loosed a fusillade at the unwary Scotts, from a distance of only a few yards with Winchester rifles and not a single bullet found its way into a Scott torso. The same Cap Hatfield who shot Jeff McCoy in the head from the opposite side of Tug River, and shot Calvin McCoy in the head while Calvin was running laterally across his field of vision under the light of the moon, could manage no more than a kneecapping in this close ambush in broad daylight.

Of course, like Glen Campbell in True Grit, they did manage to kill two horses. During those years, when Donnelly says there was a vicious blood feud underway and it was “open season for killing,” the McCoy record for futility as feudists was even worse than that of the Hatfields, as they killed no one, wounded no one, and, in fact, never even killed a horse! One wonders how much bloodier Donnnelly’s twenty year blood feud would have been had the McCoys also employed the tails of cows as part of their arsenal.

The McCoys’ “cow’s tail gap” was just as real as was General Buck Turgidson’s “mine-shaft gap” in Dr. Strangelove, and it persisted throughout the period of the hostilities.

Donnelly begins on page one with his first material factual misstatement: “In the Union corner was Randolph McCoy, leader of the McCoy clan.”[8] Ran’l McCoy was, of course, in the Confederate army. In fact, the record shows that he served in the same two units that Devil Anse served in–The Virginia State Line and the 45th Virginia Infantry. The statement that Ran’l was the “leader of the McCoy clan” is laughable. No one—not even Donnelly—has ever said that Ran’l McCoy ever led anyone anywhere at any time in his life. Yet, we see him referred to as “the leader of the McCoy clan” in writings from 1888 to 2013. This is in spite of the fact that Truda McCoy, the McCoy family historian, stated plainly that he was not the leader of the clan.

With Donnelly, it is all downhill from page 1 forward. On page two he says that Bill Staton, the unfortunate hog trial witness, was married to a Hatfield, which is not true. He said that, as a result of Ellison Hatfield pushing for the prosecution of Sam and Paris McCoy for killing Staton, “He (Ellison) was hated by all the McCoys.” Sam McCoy, one of the two who were prosecuted in the Staton killing, wrote: “If I ever had a friend in the world Ellison Hatfield was.”[9]

Donnelly says that the affair between Johnse and Roseanna started at the 1880 election, and continued “through the next two or three years.”[10] Johnse married Roseanna’s cousin, Nancy McCoy, six months after the 1880 election.

Donnelly then goes into the war records of the Hatfields and botches that one, too. He says that when Devil Anse joined the Confederate army, he joined the Logan Wildcats. Anse joined first the Virginia State Line, in 1862. The Logan Wildcats were a militia unit that became the 36th Battalion, Virginia Infantry, and remained so for the duration of the war. Anse was never a member of that unit. He says that Ellison was in Pickett’s charge at the battle of Gettysburg, and was with Lee at Appomattox. Ellison was in the same 45th Virginia as Anse, and that unit was not at Gettysburg. Ellison had deserted before Lee surrendered.

Donnelly gets the events of Election Day, 1882 and the two days following pretty well right. This is understandable, because he says that he got the story from Ransom Hatfield. Then he immediately relapses with the aforementioned quote about “open season” for the McCoys to shoot Hatfields for twenty years.

Donnelly has a penchant for giving the ages of the characters in his tale, and almost every age he gives is wrong! He says that Ran’l McCoy, born in 1825, was sixty-three years old in 1882.

In the summer of 1887, Donnelly says that the Hatfields shot at Ran’l as he stood in the door of his cabin. Again, the hapless Hatfields missed him completely. Donnelly, who says that he visited the McCoy home place, should never have told this tale the way he told it. Ran’l McCoy’s house sat in the mouth of a hollow, with the base of the hill and its tree line no more than 10 yards from the house. His outbuildings sat even closer to the woods on the other side of the hollow. Instead of having the would-be assassin in the timber, within a close pistol shot of Ran’l whenever he went about his daily chores, Donnelly has him positioned on the hillside across Blackberry Fork, a shot of more than a hundred yards.

All of the fabricated feud yarns make the actors appear either bloodthirsty or stupid, or both. If Devil Anse, five years after he more than evened the score by executing the three killers of his brother, was gunning for Ran’l McCoy, he was bloodthirsty. If he sent a man to position himself as Donnelly has him positioned, he was stupid.

Donnelly has the New Year’s, 1888 raid on the McCoy home occurring after the case had gone to the supreme court, when, in fact, it occurred several months prior to the case being heard by any court. Donnelly says that the raid was for the purpose of “wiping out the prosecuting witnesses.”[11] Of course he doesn’t explain why they left alive the only person at that home who could place any Hatfield in the group that killed the three boys, Sally McCoy.

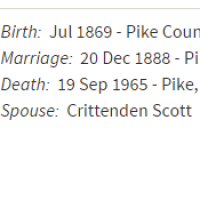

Just as Donnelly told his readers that he researched the Election Day events on Blackberry by visiting Ransom and Jeff Hatfield, he now establishes his bona fides on the New Year’s raid by telling us that he visited that site also. Here he doesn’t do quite as well as he does with Blackberry Creek, where he at least got the names of the Hatfield brothers right. He says that he visited “Mrs. Crit Scott and her maiden daughter, Miss Pricy Scott.”[12] Mrs. Crit Scott was Pricy Scott. Her daughter, who lived with her, was named Mertie. I cannot attest to Mertie’s maiden status, as does the preacher, but I can say that she never married.

Donnelly gets the events of the bloody affair pretty much right, which means that he probably did talk to the Scott ladies. His version does not differ materially from what the Scott ladies told me in the conversations I had with them in the same time period as his visit, while my sister rented a small house on the Scott property. He did not get as much detail from them as I did, but he only visited once. His failure to get the names might simply be a case of shoddy note-taking.

What Donnelly says immediately after describing the New Year’s raid, while appearing to be just thrown in as an after-thought, is vital to understanding how most feud writers write on “the feud.” Donnelly says: “On the evening of February 6, 1955, I ate supper with Mr. and Mrs. Paul McCoy at Matewan. Paul McCoy, deacon in Matewan Baptist Church, is the grandson of Calvin McCoy.

“I showed him a picture of the dornick gravestone at the head of his ill-fated grandfather’s grave. He did not know where his kinsman was buried until I showed him the picture of the grave marker which I got at Heidelberg, Germany late in 1945, while there on duty at Seventh Army Headquarters in World War II. Calvin McCoy’s grave is the only marked grave of a McCoy victim in the bitter feud.”[13](italics mine)

I cannot over-stress the importance of the italicized words. Here we see the great contradiction in the feud stories laid bare. On the one hand we are told that Ran’l McCoy was the leader of a great clan that was engaged in a decades-long blood feud during which it was “open season” for killing Hatfields, and then the same writer tells us that the grandson of a victim of “the feud,” Calvin McCoy, and a great-grandson of the great clan leader, Ran’l McCoy did not even know where his grandfather was buried! Paul McCoy, a middle-aged man at the time, lived about six miles from where his grandfather, Calvin McCoy, was buried, and he didn’t even know where the grave was! That being the case, it is virtually sure that Paul McCoy had no idea as to the location of the unmarked grave of the “clan leader,” Ran’l McCoy.

The two main things to be gleaned from this are, first, Donnelly is so sure that only a minuscule handful of people knew in 1955 where the McCoys were buried, that he had enough confidence to state that a grandson of a feud victim, living only about six miles from his grandfather’s grave did not where the grave was. Donnelly’s confidence was well-founded, because I can testify first-hand that one could count on the fingers of one hand all the people on Blackberry Creek who knew where Calvin McCoy was buried as of 1955.

Second, he had enough confidence that no one would take the trouble to research the records that he manufactured that grandson. Paul McCoy, who was a Deacon in the Matewan Baptist Church in 1955, was the son of James C. McCoy, who was the son of Pendleton McCoy. He was very distantly related to Calvin McCoy.

Since the Costner movie came out, whenever I tell someone that only a handful of people I knew who lived on Blackberry Creek during “feud times” would even talk about it, and even fewer had any detailed knowledge about it, I see an incredulous look on their faces. They just can’t believe that it is true. When I tell them that my grandfather, Phillip McCoy, a grand-nephew of Sally McCoy and a cousin of Ran’l McCoy, had no idea where any of Ran’l’s family was buried, and knew not a single person who attended Ran’l’s funeral, I think most doubt my honesty. If they only knew that the grandson of Calvin McCoy, living six miles from his grandfather’s grave, had no idea where any of Ran’l’s family was buried, maybe I wouldn’t have had such a credibility problem. I have recently started showing folks what Donnelly wrote on pages 11 and 12, showing them that Donnelly wrote that not even the grandson of Calvin knew where Calvin was buried, and no one doubted him enough to check the genealogy and see that he was prevaricating about the grandson. This usually at least partially digs me out of the credibility hole dug for me by Costner, Alther and King.

People who have seen Kevin Costner’s movie or read either of the super-sized recent books by Lisa Alther or Dean King know far more about “the feud” than did either Paul or Phillip McCoy. They also know more about “the feud” than either Ran’l or Calvin McCoy. This is true, simply because there never was a Hatfield and McCoy feud, as that term is defined in any dictionary, or as it is represented in the movie and the books.

I knew where Calvin McCoy was buried, because my sister rented a house directly across the creek from the grave, next door to Pricy Scott, but I doubt if more than two or three people living on Blackberry Creek knew where Calvin was buried. I am certain that no one on Blackberry knew in 1955 where Ran’l was buried—including me.

Donnelly then digresses for about three pages, talking about all the people who died in the feud. He includes people who were killed as far from the Valley as Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, and as late as 1912. Then he says that there were many more than he mentioned who were killed in the feud—about three dozen in his estimation. In this section he again ventures into the matter of ages and dates, and gets all of them wrong, except for the New Year’s raid. He has the ages at death of both Ran’l and Devil Anse wrong, as well as the month and year of the hanging of Ellison Mounts.

Is anyone wondering yet why Dean King cites this little book at least nineteen times as a factual source in his “True Story?” If not, just stick around.

Donnelly then gives us his rendition of the tale of the cow’s tail. He says that it was “cut off close to the cow,” on the day of the event, which means it was of maximum length and of full un-dehydrated weight. In Donnelly’s version, the result was exactly what anyone would expect; Mary Daniels was beaten to death! Of course that didn’t happen, as Mary Daniels showed up three years later in Pikeville to sign one of Cottontop Mounts’s confessions, had four more children and lived well into the twentieth century.

Donnelly starts the cow’s tail tale off with the correct names for the victims. Then he switches the Daniels name to Staton, and keeps them as Statons for several paragraphs. I’m sure that he didn’t have an editor, and there are times when I wonder if he even re-read his writings before publishing them.

On page 23, Donnelly relates again his visit with Pricy Scott. When he told of the visit, on page 10, he correctly stated that Pricy was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Aly Farley. Now, only thirteen pages later, he says: “Mrs. Scott’s father was Granville Farley.”[14] Donnelly ends that section with a paragraph that is a classic:

“Lots of books have been written on this feud. With few exceptions much that has been written was written afar off and is full of glaring errors.”[15] I have read Donnelly’s little book about two dozen times, and I still laugh out loud at that sentence.

Some of the errors in Donnelly’s book are superfluous “factoids” thrown in to impress the reader with his detailed knowledge, but many backfire on him. He twice refers to Dyke Garrett, who baptized Devil Anse as “a Hardhelll Baptist,” when Uncle Dyke was a preacher in the Church of Christ—about as far from a Hardshell Baptist as one can go, theologically speaking.

Most of the errors, as in other feud books, come from repeating old front-porch tales as fact. His fatal beating of Mary Daniels with a cow’s tail and his inclusion of the time-worn fable of

Abner Vance’s sojourn in Tug Valley at a time when Vance was in jail in Virginia are two prime examples.

While I consider the great bulk of Donnelly’s errors to be benign in that he is repeating what was heard on front porches throughout the Valley over the years, or he is depending on either bad notes or bad memory, his repeated insistence that he is writing the truth gives me grave doubts. In addition to his earlier cited indictment of other writers’ errors, he says that what he has written here is “the result of close to 40 years of careful study of the notorious subject. Much of the material presented has resulted from far-flung field tips and copious conversations with many of those who saw the history being made.”[16]

Of course all the tall tales from previous writers, all the way back to the 1888 newspaper stories are not history, and Donnelly should not have insisted that they were.

[1] Donnelly slightly misstates the quote, which was, “ Tolb, Election Day ain’t no day to settle a debt.” The other two quotes Ransom gave the writers were what his father related that was said at the beginning of the Election Day fight. Tolbert McCoy said, “I’m Hell on earth,’ and Elliosn Hatfield answered, “You’re a damn shit-hog.”

[2] Robert C Byrd, later a long-time Senator, was both a state klan leader and the adult class Sunday School teacher in Donnelly’s church.

[3] Donnelly, Shirley, The Hatfield-McCoy Feud Reader, Foreword.

[4] Donnelly, 7.

[5] Donnelly, 14.

[6] Donnelly, 10.

[7] Donnelly, 9.

[8] Donnelly, 1.

[9] McCoy, Samuel, Squirrel Huntin’ Sam McCoy: His Memoir and Family Tree, 27.

[10] Donnelly, 3.

[11] Donnelly, 10.

[12] ibid

[13] Donnelly, 11-12.

[14] Donnelly, 23.

[15] Donnelly, 25.

[16] Donnelly, 21.

[i] Donnelly slightly misstates the quote, which was, “ Tolb, Election Day ain’t no day to settle a debt.” The other two quotes Ransom gave the writers were what his father related that was said at the beginning of the Election Day fight. Tolbert McCoy said, “I’m Hell on earth,’ and Elliosn Hatfield answered, “You’re a damn shit-hog.”

[ii] Robert C Byrd, later a long-time Senator, was both a state klan leader and the adult class Sunday School teacher in Donnelly’s church.

[iii] Donnelly, Shirley, The Hatfield-McCoy Feud Reader, Foreword.

[iv] Donnelly, 7.

[v] Donnelly, 14.

[vi] Donnelly, 10.

[vii] Donnelly, 9.

[viii] Donnelly, 1.

[ix] McCoy, Samuel, Squirrel Huntin’ Sam McCoy: His Memoir and Family Tree, 27.

[x] Donnelly, 3.

[xi] Donnelly, 10.

[xii] ibid

[xiii] Donnelly, 11-12.

[xiv] Donnelly, 23.

[xv] Donnelly, 25.