Otis Rice’s “Hatfields & McCoys”—A Yarn or History?

Preface

The West Virginia Encyclopedia says of Otis Rice:

One of West Virginia’s most published historians, Rice was the author of The Allegheny Frontier, which received an Award of Merit from the American Association for State and Local History; Hatfields and McCoys; Frontier Kentucky;Charleston and the Kanawha Valley; History of Greenbrier County; Sheltering Arms Hospital; and West Virginia: The State and Its People. He co-authored with Stephen W. Brown, West Virginia: A History, a college text; The Mountain State, a middle school text; as well as A Centennial of Strength: A History of Banking in West Virginia.

Rice served as president of the West Virginia Historical Society (1955–56) and the West Virginia Historical Association (1967–68); book review editor of West Virginia History (1976–79); member of the editorial board of Filson Club Quarterly (1985–87) and the board of advisers of the WVU Library (1988–95); vice chairman of the Kanawha County Bicentennial Commission (1986–90); and first vice president, West Virginia Historical Education Foundation (1992–2003). Among other awards, he received the first Virgil A. Lewis Award of the West Virginia Historical Society (1991) and the first Governor’s Award for Outstanding Contributions to West Virginia History or Literature (1999). He received an honorary doctorate from West Virginia University in 2000. On July 22, 2003, Rice was named West Virginia’s first Historian Laureate. http://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/77

So far as I know, that is all true.

The University Press of Kentucky says of his book, “The Hatfields & the McCoys:”

“The Hatfield-McCoy feud has long been the most famous vendetta of the southern Appalachians. Over the years it has become encrusted with myth and error. Scores of writers have produced accounts of it, but few have made any real effort to separate fact from fiction. Novelists, motion picture producers, television script writers, and others have sensationalized events that needed no embellishment.

Using court records, public documents, official correspondence, and other documentary evident, Otis K. Rice presents an account that frees, as much as possible, fact from fiction, event from legend. He weighs the evidence carefully, avoiding the partisanship and the attitude of condescension and condemnation that have characterized many of the writings concerning the feud.

He sets the feud in the social, political, economic, and cultural context of eastern Kentucky and southwestern West Virginia in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. By examining the legacy of the Civil War, the weakness of institutions such as the church and education system, the exaggerated importance of family, the impotence of the law, and the isolation of the mountain folk, Rice gives new meaning to the origins and progress of the feud. These conditions help explain why the Hatfield and McCoy families, which have produced so many fine citizens, could engage in such a bitter and prolonged vendetta.” http://www.kentuckypress.com/live/title_detail.php?titleid=1989#.VNI0eJ0c58E

Almost none of that is true, and I will prove it. The claim: “Using court records, public documents, official correspondence, and other documentary evident, Otis K. Rice presents an account that frees, as much as possible, fact from fiction, event from legend. He weighs the evidence carefully”– is provably false in detail.

Rice ignores the actual record on most of the events and people he describes, and directly conflicts the record in many places. While rarely referring to the historical record, Rice depends almost entirely upon newspapers and prior feud yarns for his “facts.”

He warns repeatedly against depending upon newspapers, and then cites newspaper reporters as fact sources more than one hundred fifty times!

On the first page of his Preface, Rice writes: “In addition, many newspaper accounts were so biased or so grossly inaccurate that they must be used with considerable discrimination.” He repeats the caveat about accepting newspaper reporters as fact sources many times in the book. Then, throughout the book, he indiscriminately uses newspaper reporters as fact sources, even when they conflict directly with the historical record.

Because he was West Virginia’s “Historian Laureate,” and because his book was published by the University of Kentucky, I consider Otis Rice to be the biggest impediment to getting the real history of the Tug Valley in the feud era out to the public.

I hereby challenge any faculty member from any college or university in either West Virginia or Kentucky to publicly debate me on the question: “Is “The Hatfields & the McCoys,” by Otis K. Rice, real history, or just another feud yarn.”

Rice and the Civil War

On page 10 Rice writes: “The Hatfields favored the Confederacy, as did the majority of the McCoys, but a few of the latter supported the Union.” That is undoubtedly a deliberate misstatement of the facts, as anyone doing any research on the military associations of the families would know that more than two thirds of the Kentucky McCoys who served wore Union blue. The error became more important than it should have been, simply because it was relied upon by Altina Waller, resulting in the only material error in her fine book.[1]

Rice has a thoroughly garbled recounting of the Civil War history of the two families, getting almost nothing right except for the fact that Devil Anse deserted. He even includes the ridiculous claim that Devil Anse was a member of the Logan Wildcats. The Logan Wildcats were Company D of the 34th Virginia Infantry. That unit never operated within a hundred miles of Tug River, and Devil Anse was never a member of the unit. Rice then compounds his error by saying that Ran’l McCoy was also a Logan Wildcat. (p.11)

Rice lets us know that he was familiar with the record, by citing several post war lawsuits, filed against raiders of various farms. He leaves out the most important ones, which featured Union soldiers raiding the farms of Union supporters, George and James Hatfield.

Rice defies the plain record repeatedly in describing Asa Harmon McCoy. He says that Asa Harmon sat out the first two years of the War and enlisted in the 45th Infantry in late 1863. He once again says that in joining the Union cause Harmon was going against “most of his own family,” [2]which is patently false.

Rice says that when Harmon came home near the end of 1864, “his former friends and neighbors did not extend him a cordial welcome.” (p.13) This is outrageous! I have identified more than seventy-five men from Peter Creek who served the Union, and less than half a dozen who served the Confederacy.

Rice says that Jim Vance, a member of the Logan Wildcats, told Harmon that “the Logan Wildcats would soon pay him a visit.”(13) There is absolutely nothing in the record which associates Jim Vance with the Logan Wildcats or any military organization that included Devil Anse Hatfield.

Rice then says: “Knowing that to remain at home would mean almost certain death, Harmon hid out in a nearby cave. There they found Harmon, lame and suffering from lung troubles, and killed him.” (13) That is false in detail. Harmon was literally surrounded by his fellow Unionists, many of whom had deserted the 39th Kentucky earlier in that autumn. None of his near neighbors were Confederate. Yet, Rice says that Harmon was so scared of the Rebels that he abandoned his home and family and crawled into a hole in the ground.

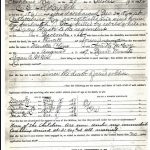

Rice gives a footnote referencing the medical record of Asa Harmon McCoy. That medical record proves clearly that everything Rice wrote is false. Far from “sitting out the first two years,” Harmon was in the Home Guard and was seriously wounded in the chest in February, 1862. In November of that same year, he was captured by the Virginia State Line cavalry—including Devil Anse Hatfield—and sent to Libby Prison in Richmond. Paroled and discharged in April, 1863, he returned home, still recuperating from the old chest wound. In October of 1863, is chest wound healed, he traveled to Ashland and enlisted in the 45th Kentucky Infantry.

Discharged on Christmas Eve, 1864, Harmon immediately re-enlisted and was sent home on furlough. He was, according to the sworn testimony of his widow, “killed by rebels while on his way back to his regiment.”

Rice cites Asa’s army medical record, which says he was shot in a skirmish “near Sandy River” in February, 1862, then captured by Federals in December of that same year. He was released from the Union hospital in Annapolis, Maryland in April, 1863, with his chest wound still oozing, per the written statement of the military doctor in the official records, and then says that Harmon sat out the first two years of the war. Preposterous!

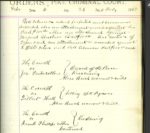

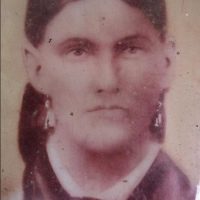

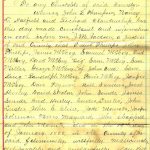

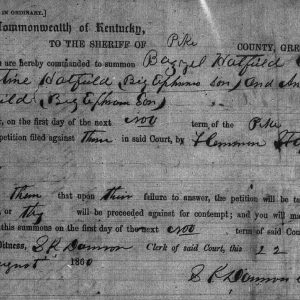

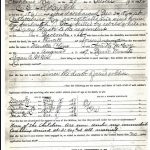

Here is the sworn statement of Harmon’s widow, Martha (Patty) McCoy, wherein she tells how he died:

That is also in the medical record cited by Rice. Here, as in so many places in the book, Rice deliberately ignores records he admits that he has seen, and repeats the “feud yarn” as history!

Asa Harmon and Jim Vance

Rice then says that, while some thought Devil Anse “murdered” Asa Harmon, “More likely the real culprit was Jim Vance, a close associate of Devil Anse…The tall, heavy-set, dark-bearded Vance, himself a later casualty in the feud between the Hatfields and the McCoys, had a reputation, even among his rough associates, for ruthlessness and vindictiveness.” (14)

Rice gives absolutely no foundation for that scathing indictment of Jim Vance; he simply states it all as if it were well-established fact. The record proves it false in detail.

First, there is absolutely nothing in the record that shows Jim Vance to be “a close associate of Devil Anse.” However, there is much in the record showing Vance to be a close associate of the family of Asa Harmon McCoy. The record clearly depicts a man who was highly respected in his community—the mirror opposite of the reputation Rice gives him.

In 1870, Jim Vance was elected Constable of the Magnolia District. His neighbors obviously did not consider him a bad man. In 1883, at the zenith of Rice’s blood feud, the Logan County Court appointed Jim Vance Justice of the Peace when the incumbent resigned. The Logan ruling elite certainly didn’t share Rice’s assessment of Vance, and the court was hardly made up of “rough” associates.

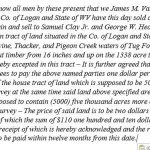

Four substantial land-owners in the District, none of whom were related to Vance, signed twenty-five hundred dollar bonds for Vance, as seen in the document. That is equal to one hundred fifty thousand dollars in gold today.

A list of the four most important figures on each side in the feud story would have, on the Hatfield/West Virginia side: Devil Anse, Johnse and Cap Hatfield, and Jim Vance. On the McCoy/Kentucky side would be: Ran’l and Jim McCoy, Frank Phillips and Perry Cline. Of those eight men, ONLY Jim Vance was never indicted for a crime in his entire life!

There is much more in the record about Jim Vance and his general reputation, as well as his association with the family of Asa Harmon McCoy; so much in fact that we will only look at a single year, 1875.

In 1875, ten years after Otis Rice says that Jim Vance murdered Asa Harmon McCoy, Perry Cline, brother of Martha (Cline) McCoy, the widow of Asa Harmon, became sheriff of Pike County. The large bond required of someone entering that office was signed by three men. These included two of the richest men in Pike County, O.C. Bowles and the foster father of Perry Cline, Colonel John Dils. The other was Jim Vance, who had lived in Pike County only about a year at that time. Is Colonel Dils another of Vance’s “rough associates?”

Later that same year, Perry Cline appointed Jim Vance a deputy sheriff of Pike County, making Vance the only man who was a sworn law officer in both Pike and Logan counties during the entire era.

Does anyone—other than Otis Rice—really believe that Perry Cline thought that Jim Vance had murdered his brother in law? Is Perry Cline just another of the “rough associates” in Rice’s book?

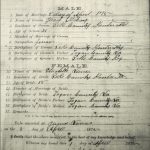

In April, 1875, Jacob McCoy, son of Asa Harmon McCoy, married Elizabeth Vance, daughter of Jim Vance. The marriage Bond was signed by Jacob’s Uncle, Perry Cline, and the ceremony was held at the Pike County home of Jim Vance.

In June of 1875, Jim Vance bought a large tract—a thousand acres—from Bill and Mary (McCoy) Daniels. Mary Daniels was the daughter of Asa Harmon McCoy. The Danielses took a note from Jim Vance for a third of the purchase price of that tract.

Does anyone—other than Otis Rice—really believe that the family of Asa Harmon McCoy thought that Jim Vance had murdered the father of the family?

There is no doubt that Otis Rice, having spent his entire professional career doing historical research, knew everything I have presented here. After all, I found it in only a few days of research. In his “Bibliographical Note” at the back of the book Rice lists all the sources one needs to find everything I have presented here, but which was omitted from Rice’s “history.”

The only logical conclusion to be drawn is that Rice intentionally ignored and distorted the record to make a man who had a stellar record and a fine relationship with the family of Asa Harmon McCoy something that he clearly—by the record—was not: the low-life murderer of Asa Harmon McCoy. This is libel of the dead, totally unbecoming of someone who made a living as a professional “historian.”

Rice on the Hog trial

Professor Rice recounts the story of the hog trial just as if it were handed down from Mt. Sinai, even though there is absolutely nothing in the record pertaining to such a trial. He gives a few daisy-chain citations, but most of it is just Rice spinning a yarn, with no support claimed for what he writes.

I believe that there was an argument about a hog involving Ran’l McCoy. The local lore on Blackberry Creek 70 years ago said it was between Ran’l McCoy and Jesse Gooslin–NOT Ran’l McCoy and Floyd Hatfield. The oldest people I talked to as a boy in the 1950’s spoke of such a dispute. None, however, recalled an actual trial.

If there had really been a dispute between Floyd and Ran’l, there was a witness very near to Floyd Hatfield’s hog pen who knew whether or not Floyd owned the pork in question. That witness was Floyd Hatfield’s landlord, the brother in law and first cousin of Ran’l McCoy, my Great, Great Grandfather, Uriah McCoy.

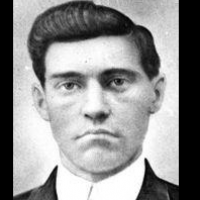

I talked regularly with two of Preacher Anse’s sons, Jeff and Ransom, as I delivered papers to them in 1952-55. Both denied such a trial ever happened. Both said that trials were rare in their father’s court, as he was usually able to mediate any arguments which arose. JP’s were paid $2/day for holding court in those days. All the payments are in the Pike County Court records. Preacher Anse was paid a total of $8 during his 4-year term, and all of it was in the first year. Preacher Anse was elected to his only term as JP in 1871. In 1875, he was elected county tax assessor, the office he held at the time Rice says he was a JP, hearing a trial over a $10 pig.

While no one can prove that a hog trial occurred, no one can prove that it didn’t; but I can prove that much of Rice’s yarn about the trial is either nonsensical or simply false.

Rice begins his tale of the hog trial with: “In the autumn of 1878 Floyd Hatfield, a cousin of Devil Anse, went into the hills, rounded up his hogs, and drove them into pens for fattening at his home near Stringtown, on the Kentucky side of the Tug Fork.” That opening statement contains several “facts.” Not one of which could possibly be known as a fact by Professor Rice. How does he know that Floyd went into the hills and rounded up his hogs? Could he not have hired a neighborhood boy to round them up? Or could the hogs not have come home on their own?

How does he know that Floyd lived at Stringtown in the fall of 1878? Floyd Hatfield is at Stringtown, on the land of Uriah McCoy, in the 1870 Census. In the 1880 Census, he is in Logan County on land he bought from Devil Anse in 1877. It is at least as likely that Floyd was in Logan as that he was in Pike in the fall of 1878.

I know that Rice got much of his hog trial tale from Charles Mutzenberger. I know this because Rice refers to my Great, Great Grandfather, as “Deacon Anse Hatfield,” and that originated with Mutzenberger. No one who knew Preacher Anse ever called him “Deacon.” There was a “Deacon” Hatfield, but it was Preacher Anse’s brother, Basil Hatfield, who served as both county judge and sheriff of Pike County.

Like Mutzenberger, Rice has large numbers of each family in attendance, but neither Rice nor any other feud writer mentions the one man whose testimony would have been dispositive of the case–Ran’l’s cousin and brother-in-law, Uriah McCoy, upon whose land Floyd lived. Rice refers to two “sides” as if an argument over the ownership of a pig was a major controversy. Rice has seen the Circuit Court records; he cites them in his Bibliographical note. He knows, therefore, that both Devil Anse Hatfield ans Ran’l McCly were involved in multiple lawsuits during the 1870’s which involved amounts equal to hundreds of hogs, but he goes along with the yarn.

Rice does not tell his readers that Devil Anse was involved in a lawsuit with Bill and Mary Daniels, daughter and son in law to Asa Harmon over eight hundred acres at the time of the hog trial. If Rice told his readers that Devil Anse was personally involved in a large lawsuit against the immediate family of the man Rice says was murdered by Anse or someone under his command, then how could he convince them that Devil Anse was concerned over a cousin possibly losing a pig to a McCoy who had served with Anse in the Confederate army.

Like Mutzenberger, Rice has a jury of twelve members, six Hatfields and six McCoys. Again, Rice must know better, but he wrote it anyway. Kentucky law—as well as that in West Virginia, where he was “Historian Laureate”—restricted a justice of the peace jury to a maximum of six members.[3] The restriction is also in Article 248 of the Kentucky Constitution. Faced with a choice between Mutzenberg’s yarn and the law, the Professor comes down squarely on the side of the yarn-spinner.

Rice cites Truda McCoy, G. Elliott Hatfield and Virgil Jones for his hog trial yarn. Neither of those writers cites anyone or anything. The Professor does not cite Mutzenberg at all, but anyone can compare pages 14 and 15 of Rice with page 16 of Mutzenberg and see that he should have.

Rice makes profuse use of what I have dubbed “The daisy-chain” in his citations. Feud books from John Spears in 1888 until Virgil Jones in 1948, were void of footnotes or endnotes. The writers wrote a story.

The books following Jones all have copious reference notes.[4] With the exception of Professor Waller, all the writers use the daisy chain. Very few notes—even in the book by the historian, Rice—are to original records.

The daisy chain always ends with a prior writer who cited nothing in support of what he wrote. Virgil Jones is the most frequently cited source for Professor Rice, and Virgil Jones cites nothing for his tale. Mutzenberg is mentioned in Rice’s Bibliographical Note as the best of the prior writers, but Mutzenberg also cites nothing in support of his yarn.

Of course the average reader is impressed by all the little numbers seen in the books, but not one in a thousand ever traces the daisy chain back to its origin, which is almost always the unsupported scribblings of a previous yarn-spinner.

The Quiet Years

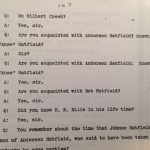

Under oath in the 1899 trial of Johnse Hatfield, Jim McCoy swore that between the 1882 lynching of his brothers and the Frank Phillips raids of December 1887, “We tried to get them arrested, but we never had any trouble.”

Rice struggles mightily to find enough “feuding” during the quiet years to maintain his feud, but ends up with a chapter only six and one-half pages long covering the entire five-plus years. More than half that chapter is devoted to the Jeff McCoy killing. In desperation he writes: “Some of them may have occasionally fired upon a member or cabin of the opposing clan.”All writers of feud books include in the feud story the November, 1886 killing of Jeff McCoy, which is not connected to the 1882 events. Then they proceed to fill the years between the lynching of the three McCoys in August 1882 and the beginning of the Phillips raids in December 1887 with manufactured feud events which have no support whatsoever in the records.

Rice shows even more desperation in his search for a feud during the years when nothing happened by including a page on the escape from the Mount Sterling jail by Montaville Hatfield, which no one—including Rice—says was connected to the feud in any way.

Rice ends up with only the “ambush of the innocents” and the “tale of the cow’s tail” to maintain his blood feud during those quiet years.

The ambush of the innocents is a tale that says that Devil Anse wanted to kill Randolph McCoy in 1884. We don’t know why Anse wanted to kill Ran’l in 1884, as nothing had happened since Anse killed three of Ran’l’s sons, which should have balanced the scales in Anse’s mind, but that is Rice’s story. Being too obtuse to realize that anyone in his household over the age of ten could get close enough to Ran’l any day as he went about his chores to easily kill him, Anse sets in motion an elaborate espionage effort to learn when Ran’l will be traveling down the road and therefore exposed to ambush.

Rice says that the Hatfields learned of an impending trip to Pikeville and set up an ambush. Unfortunately, the Hatfields didn’t even know what their adversaries looked like, and they shot two neighbors of the McCoys instead. As with all the manufactured “feud events” during the five years when nothing happened, the absence of corpses makes poor marksmanship an essential part of the tales. In this case, Rice says that the inept Hafield marksmen managed to wound only one of the two unintended targets. Like Glen Campbell in True Grit, they managed to kill both the horses.

For this fiasco in the wilds of Blackberry Fork, the Professor cites the Louisville Courier Journal and the Pittsburgh Times. The daisy chain ends with newspaper reporters here, but it is now part of “history.”

Does any reader with an IQ above room temperature not know that the Professor is spinning a yarn here, and not writing history? Consider this:

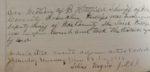

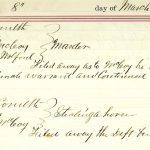

In 1878, while Perry Cline was the incumbent Sheriff of Pike County, both he and his wife, Martha Adkins Cline, were charged with assault and battery.

Sheriff Cline copped a guilty plea, paying a ten dollar fine, in order to get his wife dismissed as a defendant.

The Pike County Circuit Court Records, to which Rice refers in his Bibliographical Note, are replete with charges of assault and battery in the 1870’s and 1880’s. Many of those charges were brought against women—some of them middle-aged. Another famous “feud name,” Nancy McCoy Hatfield Phillips, wife to Johnse Hatfield and later Frank Phillips, was charged with A & B:

The court added “Johnse’s wife” to identify the defendant. Nancy was fined the exorbitant—for that time—amount of forty-five dollars upon conviction.

The women married to McCoys were not immune either:

Aunt Betty McCoy was charged with several crimes, including A&B and keeping a whorehouse. The jury was more lenient with Aunt Betty than with Nancy. She was convicted and fined ONE CENT!

Professor Rice was familiar with these records; he cites them in his bibliography. He knew that in a county where women with strong family connections were charged and convicted of assault and battery, there was no way that the most hated men in Pike County could come across the border and shoot a man and kill two horses without a charge being field. But the professor used it anyway, citing two big city newspapers.

The professor also has the venerable “tale of the cow’s tail” in his little chapter on the quiet years. He says that Cap Hatfield and Tom Wallace beat Mary Daniels, daughter o f Asa Harmon and wife of Bill Daniels, and her daughter with a cow’s tail. 33) For this yarn the Professor cites the newspaper reporter, Virgil Jones, who cites nothing or no one.

Professor Rice cites Virgil Jones, a total of forty-eight times as a fact source. Jones cites nothing in support of his yarn.

In his Bibliographical Note, Rice says that the best feud book is the one by Charles Mutzenberg, and Mutzneberg also reports that Cap Hatfield and Tom Wallace beat two women in the Daniels home. One may wonder why Rice does not use the writer he says wrote the best book. the answer is that Mutzenberg did not mention a cow’s tail, so Rice went with the more colorful Jones version. I don’t blame the Professor, because, after all, if you know you are just citing a daisy chain that ends up with a source that is unfounded, you might as well go with the one that will titillate readers the most.

Following his short chapter on the quiet years, Rice inserts a “filler chapter” twice as long on the other feuds going on in Kentucky at the same time.

On page 1, Rice refers to “battle scarred veterans of the feud,” knowing full well that there was only one “battle” involving the families of Devil Anse Hatfield and Ran’l McCoy—the New Year’s, 1888 raid on the McCoy home.

On page 3, Rice says of Ephraim Hatfield, father of Devil Anse: “Over seven feet tall and weighing more than three hundred pounds, he was generally referred to as “Big Eaf.” Ephraim’s Civil

Ep’s war record lists him as six feet even.[5]

The Historian Laureate of West Virginia should know that the appellation “Big” was almost always applied to an older man who had the same name as a younger relative. There were several younger Ephraim Hatfields in the Valley during “Big Eaf’s” lifetime.

[1] Feud: Hatfields, McCoys and Social Change in Appalachia, 1860-1900.

[2] Of the thirteen Pike County McCoys who served, nine were in the Union Army. Preston, John David, The Civil War in the big Sandy Valley,

[3] Section 2252 of the Kentucky Statutes.

[4] Truda McCoys book, “The McCoys,” has no reference notes, but it was written before Jones, although not published until 1976.

[5] Weaver and Osborne, The Virginia State Rangers and State Line, 200.