[It is fascinating how the history of the people of the Tug Valley has been fictionalized, that is falsified, at so many points. I often wonder why that is. Why is it that we have so many tales that have survived into the present, but so many of them are built on lies? The Abner Vance story is just such a lie. The Abner Vance story is in many ways a foundational story for our local history, and like so many of these tales it romanticizes a particular kind of frontier violence. If you accept the Abner Vance tale, as writer Dean King did hook, line, and sinker, then our history began with a cold blooded murder, itself a response to the mistreatment of a young girl. Sexual violence leading to homicide leading to a flight to the wilderness. Racy stuff. As Thomas points out here, the truth (poorer cousin of the legend) is more drab and more ordinary and, because of that, something we can all more easily relate to. –Ryan Hardesty]

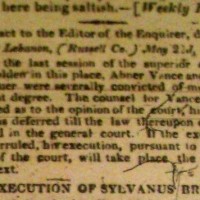

Abner Vance, the great grandfather of Devil Anse Hatfield, shot and killed Lewis Horton in Russell County, Virginia on September 22, 1817. He was hanged for the crime in Washington County, Virginia on July 17, 1819. Both the feud stories and the public records agree on the foregoing, but, on virtually every other point, the divergence between the story and the actual record is glaring.

(Abner Vance was my fourth great grandfather.)

The Abner Vance yarn is set forth succinctly on the Vance Family website:

“Abner Vance born c 1750 in NC. He migrated into the southwestern part of Virginia (Clinch River Valley, Russell Co) sometime around 1790. He was of the Baptist faith and spent much of his time preaching.

One of Abner’s daughters (and it is thought to have been Elizabeth) ran off with Lewis HORTON. After several months Lewis Horton returned with the girl and dropped her off at her parent’s home. It is said that Abner and Susannah pleaded with Lewis to marry the girl. He refused and turned to ride away. Abner went into the house and returned with his gun and shot Horton as he was riding away. Horton died a few hours later.

Abner Vance became a “fugitive”. He left Russell County that night, September 17, 1817 and traveled along the Tug and Guyandotte Rivers where he spent the next two years.

At the urging of family members Abner returned to Russell County to stand trial for the murder of Lewis Horton. Public opinion was that Abner would be “freed” due to his “reputation as a preacher”. On his arrival in Russell County, he was locked in jail and held without bail.

The first trial ended in a “hung jury”. A second trial was held in Washington County. There Abner Vance was found “guilty” of the murder of Lewis Horton and sentenced to hang. A third trial was held. Abner was again found guilty and sentenced to hang. The case was taken to the court of appeals but the lower court’s decision was upheld.

Petitions for the release of Abner Vance were circulated but to no avail. The Governor would not interfere. Abner Vance was hanged 16th of July, 1819 in Abington, Washington County VA. A short time afterwards a courier arrived with a pardon from the Governor. Susannah VANCE and her children left Russell County and migrated into the Tug, Big Sandy and Guyandotte valleys.”

Various purveyors of the feud story have reproduced this family legend, almost as seen here. The two best-selling books following the 2012 TV mini-series, by Lisa Alther and Dean King, have the yarn. Both add to it the totally false claim that Abner Vance accumulated vast tracts of land in the Tug Valley during his two-year hiatus in the wilderness, which he parceled out to his surviving progeny at his death.

The Abner Vance yarn had been thoroughly debunked for a decade when Alther and King wrote their “histories,” yet both included the old yarn just as nothing had been learned since L.D. Hatfield first published ii in his 1944 “True Story” of the feud.

In the September, 2003 issue of the Appalachian Quarterly, beginning on page 40, Grace Dotson told the real story of Abner Vance–from the court records. Anyone repeating the old Abner Vance Yarn after that time was either ignorant or willfully dishonest. Back issues are available on the Wise County Historical Society’s website.

The premier current Vance researcher, Barbara Vance Cherep, published her actual history of the case on the internet in 2007.

Ms. Cherep proves, by the court records, that the Abner Vance yarn is false in detail.

In July, 2012, Randy Marcum, a legitimate West Virginia historian who works at the West Virginia Department of Culture and History, gave a presentation which completely debunked the old Vance yarn, relying mainly on the work of Barbara Cherep.

That presentation was available on YouTube for more than a year before the publication of the book by Dean King. King was undeterred by either Cherep or Marcum, and reproduced the old yarn in a book which he said would “deflate the legends and restore accurate historical detail.” (p. xii-xiii)

Abner Vance was not a preacher. There is no record of him ever preaching, and no testimony in either of his trials that he was a preacher. The court records refer to him as “Abner Vance, laborer.”

Abner Vance’s daughter, Elizabeth already had two out-of-wedlock children in 1817, one being my great, great grandmother, Mary Vance Hatfield, and was possibly pregnant with a third. The claim that Vance was angry with Horton for debauching his innocent daughter is false. The real motive was Horton’s recent testimony against Vance’s interest in a lawsuit.

Abner Vance did not abscond to the Tug Valley immediately after the crime and remain there for two years. He was arrested shortly after the crime, and had his first court hearing on October 16, 1817, at which time he was remanded to jail, without bail, and he remained in jail every day until he was hanged. At each of his many court appearances during the twenty-two months between the crime and the execution, the court record states that he was brought from the jail to the court by the jailer. The record proves conclusively that Abner Vance never set foot in the Tug Valley during those two years.

There were two trials of Abner Vance, not three. There was no trial which resulted in a hung jury. At the first trial, in Russell County, he was convicted and sentenced to hang. He appealed on the basis that the trial judge had not allowed him to plead insanity. The appeals court set the conviction aside and ordered the lower court to try him again, allowing him to plead insanity.

Unable to find a jury that had not prejudged the case in Russell County, the second trial was moved to Washington County. Vance’s claim of insanity was not accepted by the jury, which sentenced him once again to hang for the crime.

The sentence was carried out on July 17, 1819. The newspapers reported that he addressed the crowd for an hour and a half, and accepted death with equanimity. He did not deny the crime, but argued strenuously that his punishment was excessive.

The true story of Abner Vance shows a man who, either in the heat of passion, or in a state of temporary insanity, killed a man. He then faced his crime and fought a valiant fight for his life. Losing, he then faced death in a most manly fashion. He was NOT a coward who killed a man and then absconded to the wilderness.

The struggle between history and legend continues today. In my book, “The Hatfield & McCoy Feud after Kevin Costner: Rescuing History,” I refuted the yarn in detail. On July 12, 2014, an article in the Logan Banner repeated the old Vance yarn, totally ignoring the work of Cherep, Marcum and me.

Fortunately for the side of real history, Ryan Hardesty did a series of three articles on Abner Vance for the magazine, “Blue Ridge Country.”Hatfields & McCoys, Revisited: Part 5.2 – The Legend of Abner Vance – Blue Ridge Country

Back issues are available on the Wise County Historical Society’s website.

Of course the next “True Story” churned out by the feud industry will have the old Abner Vance yarn, just as it was before the turn of the century.