(An excerpt from my upcoming book, “Nancy and Bad Frank Phillips: A Hatfield-McCoy Feud Tragedy.)

My Grandfather, Perry Dotson went to work for Frank Phillips at age 16 in 1894. Grandma Dotson, who lived about forty feet from us until she died when I was twenty-one, told me several stories about Bad Frank. According to Granny, Bad Frank “Took a liking” to the young Perry Dotson, and put him to work as a helper to his blacksmith. After a couple of years helping with the repair of tools, making and attaching horseshoes, etc., Grandpa Perry became Frank’s blacksmith.

Bad Frank was always eager to be on the cutting edge. When the coal companies formed company baseball teams in the mid-1890’s, Bad Frank organized a team and entered the league. Grandpa Perry was a natural; he “had an arm.” Perry Dotson became the star pitcher and shortstop for that team, and continued to play baseball until the last year of his life, when he died of TB at age 43.

In the post- World War I era, men who played baseball for large coal companies did not have to work during the season. They practiced and played and drew their wages. In his last years, Grandpa Perry was the star of the team for the Pond Creek Colliery

My Aunt, Kentucky Dotson Farley, was the wife of long-time Superintendent of Pike County Schools, Claude H. Farley. When she was nearing ninety years of age, I asked her what she remembered about Grandpa Perry. She thought for a minute and then said: “What I remember most is that he played baseball all the time.”

Granny said that Perry Dotson always said that Frank Phillips was “The best man I ever worked for.” She said that Bad Frank, sober, was one of the nicest men she ever knew; but, Bad Frank when he was drunk, was crazy!

She said that Frank would work from daylight to dark six days a week, and then be drunk from Saturday evening until Monday morning. In his last few years, he sometimes went on week-long benders, leaving his crew to their own devices.

Both Ransom and Jeff Hatfield told me that Bad Frank frequented the five saloons at the mouth of Knox Creek, across the river from Gray, West Virginia. Before he passed out in his rented room above Skinner’s saloon, Bad Frank usually got into a ruckus with some other patron. He was such a disruptive drunk, that the saloon-keepers would probably have barred him, had he not usually brought six or eight of his men with him. An owner could afford to have a couple of Frank’s enemies get up and leave when Frank entered, knowing that Frank had at least twice as many free-spenders with him.

One night in June, 1898, Bad Frank left Skinner’s to relieve his bladder and did not return. Grandpa Perry and two other Phillips employees went to check on their boss, and found him passed out on the ground. They thought it was just the drink, until they noticed a large pool of blood by his left leg.

Frank had been shot in the thigh. Although the femoral artery had not been severed, several smaller vessels were destroyed, and the more than half hour that had passed since Frank was shot had allowed a lot of blood to spill. Grandpa took off his belt and fashioned a tourniquet, and hoisted Frank upon his saddle, riding behind Frank and holding him erect for almost ten miles to the home of William R. “Doc” Dotson. Even though he lacked any formal education in the field, Doc Dotson was beloved as a physician in the upper Tug Valley, including Peter Creek and Knox Creek in Kentucky and Thacker, Grapevine and Beech Creek in West Virginia. Doc Dotson was the personal and family physician of Devil Anse Hatfield and his brothers. He performed procedures from setting broken bones to removing appendixes, with results about equal to those of city doctors in those pre-antibiotic years.

In 1898, after four decades of service to the community, the Kentucky College of Physicians and Surgeons, voted Doc Dotson into membership.

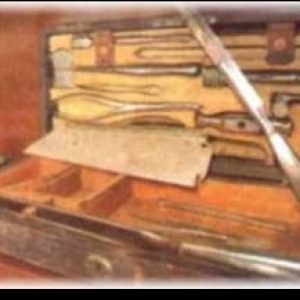

Doctor Bill amputated Frank’s leg in an effort to save him from gangrene. This is the amputation kit used by Doc Dotson to amputate the leg of Bad Frank Phillips. Photo from Dr. Garrett Dotson. Frank’s leg is buried in a separate grave, near his body.

When the operation proved unsuccessful, Bad Frank wrote his will. The will, dated five days before Frank died is in Will Book B, page 271. (Exhibit 21)

Knowing that his death was imminent, Frank wrote a detailed statement of his wishes pertaining to the extensive properties he held. He took care of all his children, by both his second and third wives, except for one, who is mentioned as “the son of Eva McCoy.” Nancy was well taken care of in the will.

Then Nancy made a mistake. Named as Executor, she should have gone to a neighboring county to get a lawyer. Unfortunately, she retained A.J. Auxier, one of the Pikeville ruling circle, and never saw a penny until she died in 1902. Her lawyers sold the property, without even announcing the sale to the public, and the lawyers bought it themselves!

According to the Court of Appeals, they paid less than a quarter of the actual value of the property. Then they split it with the estimable James York, the son in law of the late Colonel John Dils. Lawyers’ fees and administrative costs ate up the remainder, and Nancy never got a dime.

Nancy was never one to give up. Ill from advanced tuberculosis, she resorted to bootlegging to support her brood of seven children and step-children.

With the demise of Nancy McCoy Hatfield Phillips, the last eyewitness who could place most of the Phillips gang—including Ran’l McCoy and John S. Cline—at the scene of the murder of Deputy Dempsey was gone. The cabal could finally breathe easily.