Elias Hatfield, Jr.—The Rifleman

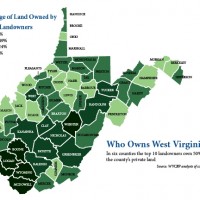

[In this essay, originally a series of shorter posts, Thomas exposes exactly how writers have all along constructed their Hatfield McCoy feud tales. He uses Dean King as the most recent example, but the same approach could be taken with any writer over the past 120 years who has ever put pen to paper and written out a description of the feud. The entire process, as far as I can tell, is most often an elaborate sleight of hand, a shell game perpetrated by writers upon an audience with untrained eyes. First, inundate the reader with footnotes, pointing out every newspaper article or family legend that has ever been put into print at any time over the past 120 years. This shows the reader that you have done your “research” and proves your authority as a teller of these tales. Second, construct any store you want from the wealth of accumulated detail. After all, who can really know what happened so long ago? -R Writers of feud stories have a choice. They can consult the actual records, or they can scour previous feud books for the most “interesting” yarns. With the lone exception of Altina Waller, all feud writers before my 2013 book opted to rely upon prior feud stories and ignore the actual records.

Writers of feud stories have a choice. They can consult the actual records, or they can scour previous feud books for the most “interesting” yarns. With the lone exception of Altina Waller, all feud writers before my 2013 book opted to rely upon prior feud stories and ignore the actual records.

In my first book, I wrote:

“Devil Anse Hatfield’s notoriety was largely won for him by his sons, who participated in the killing of six McCoys and at least seven non-McCoys during their lifetimes.”

The most recent best-seller by Dean King has several pages about one of those incidents–the 1899 killing of Humphrey “Doc” Ellis by Elias Hatfield.

The killing of Doc Ellis had some relevance to the feud story, in that the proximate cause for Elias Hatfield to be gunning for Doc Ellis was that Doc had enlisted the aid of the notorious bounty hunter, Dan Cunningham, and kidnapped Elias’s brother, Johnse, taking him “across the line” to stand trial in Kentucky for the New Year’s 1888 raid on the McCoy home.

Doc’s enmity toward Johnse arose most likely from their being competitors in the timber business, and had nothing to do with any connection between Doc Ellis and the McCoys.

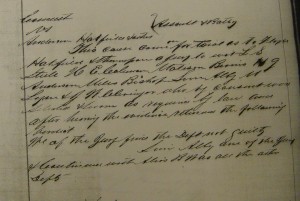

Mr. King could have learned the details of the case by simply reading the case file; but that is a lot of work, as the case file is about four hundred pages. Here is my copy of the case file:

Mr. King could read two or more of the previous feud books in less time than it would take to read the case, and the cost of the feud books would be much less. King opted for the feud stories, as his note to the section on the Hatfield-Ellis case shows:

“10. Hatfield and Spence, 251-252, drawing on writings by and interviews of Cap’s son Coleman; Andrew Chafin interview transcript, 6; and Charlotte Sanders, “Feud Was Revived in 1899 After the Killing of ‘Doc’Ellis,: Williamson Daily News, based on the Bluefield Daily Telegraph of July 4, 1899. In both the Hatfield and Spence and Daily Telegraph versions, Elias Hatfield was boarding the train as a passenger, heading to Wharncliffe, according to the latter. Though Elias was Devil Anse’s son, the Daily Telegraph referred to him as Elias Hatfield Jr., presumably to differentiate him from Devil Anse’s brother Elias. In Hatfield and Spence (252), Coleman A. Hatfield said the gun was a “new Winchester.” In Sanders’s and Chafin’s accounts, it was a pistol. In Hatfield and Spence (251), the bullet ricocheted off Ellis’s gold cuff link.”King, Dean, “The Feud,” p. 401

A reader would think that there are no better sources than newspapers and family lore and legend, as King never mentions the actual case record. This allows him to pick and choose from his many “sources” and produce the most interesting version that the sources allow. This he does, and his version of the event is false in almost every detail, as the record plainly shows.

This post will take apart King’s yarn, piece by piece, and compare it to the case record.

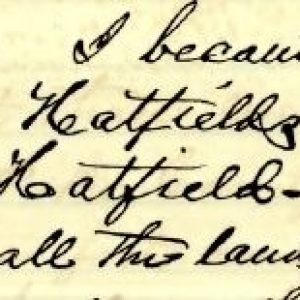

King mentions the “Junior” on the name of Elias Hatfield. As the reader can see in the first graphic above, the case is styled, “The State of West Virginia versus Elias Hatfield, JUNIOR. It was the court and NOT the Bluefield Telegraph which made that distinction. Anyone who is familiar with the usage of that time is not surprised, as many men who bore the name of an older relative who was NOT their father were designated as “Junior” in legal documents.

In the Torpin case, which deals with the land on Grapevine Creek that the feud yarns falsely claim was “taken” from Perry Cline by Anse Hatfield, the issue was the part of the land owned by the two sons of Perry Cline’s brother, Jacob. One of them was named for his uncle, Perry, and is referred to throughout the case file as “Perry Cline, Junior.”

Of course the feud writers are not familiar with that case, because it is about the same length as the case under consideration. No one expects a feud writer to devote the time to reading such voluminous records.

(Note: The reader should be mindful of the fact that Dean King promised in his “Author’s Note,” to “correct the record, to deflate the legends, to check the biases, and to add or restore accurate historical detail.”)

Feud writers are not constrained to using only newspapers and prior yarns as support for their tales. When needed, a “source” can be conjured up out of thin air. In this case, the imaginary source is N&W call boy, Andy Chafin.

This ability to invent sources allows the writer to give minute details, such as location, time of day and even conversations between the fictitious characters. It is just such detail that causes prestigious reviewers such as The Boston Globe and Professor Clyde Milner to laud Mr. King for his “meticulous research.” But it is almost entirely FICTION!

There was an N&W call boy there that day, but his name was Ed Guntner, not Andy Chafin. And he was not sitting in the car, but was outside, standing just below Doc Ellis when he was shot. Of course anyone who was so close to the shooting would be called as a witness, and here is the testimony of call boy, Ed Guntner:

E.K. Guntner, sworn for the defence, testifies as follows:-

Examination by Governor E.W. Wilson:-

Q: What is your given name.

A: Ed.

Q: How do you spell your name?

A: Guntner.

Q: What are you employed at?

A: Call Boy at Gray Yard.

Q: What were you employed at July 3rd of this year?

A: I was Call Boy there.

Q: Employed by the Norfolk & Western?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Where abouts?

A: At Gray.

King says that Elias Hatfield, like the imaginary call boy, Chafin, also worked for the N&W Railroad, as a railroad security officer. The case record tells us about a dozen times what Elias Hatfield was doing for a living at the time. He was running his saloon on the Kentucky side of Tug River, opposite the Gray railroad yard.

Q: How long have you known Elias Hatfield?

A: Three and one half months.

Q: Were you ever in his saloon frequently?

A: I was in his saloon probably twice before this occurred.

Q: Did you drink with him?

A: No, sir he did not.

Q: Did you drink?

A: Yes sir.

Every witness called by the defense was asked on cross-examination if he ever visited Elias’s saloon. Witnesses testified that Elias came across the river to Gray every day to pick up ice for his saloon.

Cross Examination by Attorney J.S. Marcum:-

Q: Did you see Hatfield around there before you head the shooting?

A: No, sir.

Q: Had you seen him around there frequently, around your place?

A: He was up there nearly every morning to get his ice.

Q: Do you know whether he came there that morning to get ice?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: How do you know it?

A: It came billed to him.

Q: That day?

A: Yes, sir.

Readers of Dean King’s feud yarn think that the saloon-keeper, Elias Hatfield, was a security officer for the N&W Railroad. The record shows that Elias owned Skinner’s saloon, just across the river in Kentucky, and that ice was shipped to him every day,billed to Elias Hatfield.And they are told that it is history!

Mr. King’s yarn continues with a description of the actual shooting of Doc Ellis. It is false in detail, as proven by the record.

King writes:

“Chafin saw Ellis rush onto the platform and raise a pistol, and he shouted, “Look out, ‘Lias!” The passenger with whom Elias was talking saw what was happening too and shoved Elias aside. Elias, dropping out of the way, pulled out his pistol and fired. Some witnesses would say that only one gun fired, but Chafin saw two flashes. Elias’s shot, taken in haste, was off the mark but not by much: the bullet struck Ellis’s wrist, broke it, ricocheted into his neck, severed his jugular vein, and exited through the top of his head. The wealthy timberman fell to the platform, dead before he hit.”

The story says that the fictitious call boy, Andy Chafin, said that Ellis had a pistol. The real call boy, Ed Guntner, said Ellis was aiming at Elias with a Winchester rifle when Elias shot him. He testified that he took the rifle into the depot and gave it to his boss. Here’s that man’s testimony about Ellis’s weapon:

Q: After the shot was [sic] where were you?

A: When the shooting took place?

Q: Yes, sir?

A: I was in the office, I had been out to the train and had turned back in the office to write out some tickets. I went out again and I saw some man lying on the second class car platform.

Q: Did you see a gun brought into your office?A: The Call Boy brought a gun into my office.

Q: What boy?

A: Edward Guntner.

Q: Gunther or Guntner?

A: Guntner.

Q: He brought a gun into your office?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: What kind of a gun was it?

A: It was a rifle; repeating rifle.

Q: Did you notice the caliber of it?

A: I cannot say what the gun used.

Q: What was done with it?

A: I asked him to let me see the gun, and he handed it to me, and I opened it.

Q: Then what?

A: I opened it and threw and empty shell out of the chamber.

Then King says that Elias shot Ellis with a pistol. Several witnesses testified in detail about the weapon Used by Elias. It was a .45-90 Winchester rifle, which was introduced into evidence in court, and examined by several witnesses, who identified it as the rifle used by Elias. Of course the Winchester used by Ellis was also introduced into the case, and was examined in the courtroom. But, in King’s tale, they both used pistols.

Then we see more of the minute detail which earns Mr. King so many plaudits from people who know nothing of the real history, when he writes that the bullet “exited through the top of his head.” That is a gory result, but it is entirely false. There was a doctor on the train, in the same car as Ellis, and he examined the body immediately after it was carried into the depot. The doctor testified that the bullet did NOT exit!

Cross examination by Governor E.W. Wilson:-

Q: Doctor, which of these wounds that you speak of, did you see first?

A: This one in the center of the neck.

Q: Why did you speak to the jury that you had seen the one in the shoulder first, before you spoke about the one in the neck?

A: It came into my mind first.

Q: Do you know that as a physician, that the wound he received in the neck would have proved fatal?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: Did you see that missle that went in there (Illustrating). Do you know whether it struck the verterbrae or not?

A: When we were using the probe it made a restriction like a loose bone or some other solid substance, and I took it to be the shoulder blade.

Q: When you probed, you thoughts the bullet that went in, came out at the shoulder blade?

A: It did not come out.

Q: If it did come out, you did not see it?

A: No, sir.

Q: You never saw it?

A: No, sir.

Q: But you probed in there?

A: Yes, sir.

King’s sttement that Ellis fell dead is true. Everything else is totally false, by the record. But it’s a good story, and, where “the feud” is concerned, that’s all that matters.

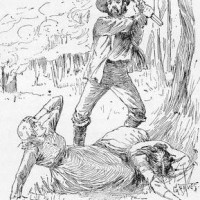

When I asked Google for images of “The Rifleman” I get a screen full of results. The one at thed top of this article was chosen deliberately, because it shows the exact pose of Elias Hatfield when he fatally shot Doc Ellis.

Elias Hatfield was on his daily trip across Tug River from his saloon in Kentucky to get ice to cool his beer. He had a letter to mail, but the post office had already taken the day’s mail to the mail car on the train. So, Elias walked alongside the train to mail his letter at the mail car.

Elias gave his letter to the man in the mail car and started back toward the depot. As he passed the second class coach, which was just behind the combination baggage/mail car, Doc Ellis was standing on the steps at the rear of the second class car. From a distance of only five or six feet, Elias said, “Doc Ellis, you son of a bitch, I bet you can’t take me the way you took my brother, Johnse.”

Elias had his Winchester in his hand, pointing down at the ground. Doc had a .38 Smith & Wesson in his right hip pocket, and several witnesses said that his hand went there, but he did not pull the pistol out of his pocket. It was seen only when the body was examined in the depot after he was dead.

An elderly gentleman, Captain Parrill, took Elias by the arm and started leading/pushing him away from Ellis. Ellis said, “Maybe I am a son of a bitch,” and walked back into the car.

The man had led Elias across one set of tracks, about 20-25 feet from the back of the car when Ellis reappeared in the doorway with his Winchester at his shoulder, taking aim at Elias. Elias wheeled, and with the butt of his rifle near his right hip, shot Ellis dead center. The bullet hit Ellis’s left wrist as he aimed his own rifle, shattered the radius bone and deflected slightly upward, striking him near the center of the neck, just above the collar bone.

Two witness testified as follows: The first paragraph is the testimony of Captain Parrill, and the second is the Call boy, Edward Guntner.

Q: You came down on which side?

A: I came down here (Illustrating) and caught him by the arms and pushed him back.

Q: How did you take hold of him?

A: I just caught him this way (Illustrating) and pushed him back, and told him that “he could not have any trouble here.”

Q: Push me back just exactly as you did Mr. Hatfield.

A: I shoved him just this way (Witness places his hand on Governor Wilson’s arms and pushed him backward.)

Q: Now I want you to show me how Hatfield threw his gun around and shot.

A: As I pushed him around his gun came in range and he fired in this shape. (Witness places the stock of the gun near his thigh, imitating how Hatfield held his gun when he fired.) He never put it to his shoulder.

Q: What did Hatfield do, if anything, in going away from the car?

A: He did not do anything.

Q: Did you see him at any other time bring it up in both hands?

A: No, sir.

Q: Then he did not have it in both hands?

A: I did not see him.

Q: You watched him?

A: Yes, sir. I do not know as I watched him all the time. I never did see him bring the gun up in both hands.

Q: You never did see him bring the gun up in both hands?

A: No, sir.

Q: What position did he bring it up in when he shot Ellis?

A: He had it in both hands then.

Q: Did he have it up to his shoulder?

A: No, sir.

Q: How did he have it?

A: I think he had the stock under his arm.

Q: You could see that?

A: I do not think he had it up to his shoulder.

Q: At that time you were looking immediately at him?

A: Yes, sir.

Q: You could look at him and see that he had it under his arm?

A: I am not positive about it. I think so.

If you reconstruct it, you will realize that Elias’s bullet would have hit Doc Ellis in the breast bone, had his left arm not been extended on his rifle. Of course Dean King could not tell his readers that Elias Hatfield could wheel and, in one motion, shoot a man dead center, without even bringing his rifle up to aim it. He couldn’t do that, simply because he had earlier written that seven Hatfields set up an ambush only thirty feet above the road and emptied their Winchesters at three men riding abreast without a single torso hit.

Hatfields who fire half a hundred shots from a position only thirty feet off the road without a single shot finding a victim’s torso, can’t then turn around and shoot a man dead center without even raising the rifle to take aim.

Hatfields and McCoys who can’t hit a barn door exist only in feud fairy tales. In reality, if Sam McCoy or Elias Hatfield shot at you with a Winchester, you were in a world of hurt. Count on it!

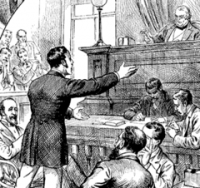

As Elias Hatfield was probably only a fraction of a second from being shot when he killed Ellis, one would think that a plea of self-defense would work, but it didn’t. Elias started the altercation by cussing Ellis, while holding a Winchester in his hand. The judge instructed the jury, properly so, that if they believed that Elias had instigated the fracas, they might find that he had forfeited a claim of self-defense.

Elias was not helped by the testimony of several witnesses that they had heard him say that if he ever laid eyes on Doc Ellis, one of them would die. One might argue that Elias Hatfield did not go to prison for shooting Doc Ellis, but, rather, for having a big mouth!

While I believe that Elias was guilty of a crime, simply because he started it, I think it was manslaughter—not the second degree murder he was tagged with. Elias got twelve years in the penitentiary, but the governor obviously agreed with me, pardoning him less than two years later.

I think the real story is at least as good a tale as is the fictional yarn in the feud book.

Finally, we will take another look at an earlier quote from Dean King:

“10. Hatfield and Spence, 251-252, drawing on writings by and interviews of Cap’s son Coleman; Andrew Chafin interview transcript, 6; and Charlotte Sanders, “Feud Was Revived in 1899 After the Killing of ‘Doc’Ellis,: Williamson Daily News, based on the Bluefield Daily Telegraph of July 4, 1899. In both the Hatfield and Spence and Daily Telegraph versions, Elias Hatfield was boarding the train as a passenger, heading to Wharncliffe, according to the latter. Though Elias was Devil Anse’s son, the Daily Telegraph referred to him as Elias Hatfield Jr., presumably to differentiate him from Devil Anse’s brother Elias. In Hatfield and Spence (252), Coleman A. Hatfield said the gun was a “new Winchester.” In Sanders’s and Chafin’s accounts, it was a pistol. In Hatfield and Spence (251), the bullet ricocheted off Ellis’s gold cuff link.”

Considering the totality of these three end notes, it is obvious that Dean King intends to convey to his readers that there is no way to know the truth about the event, so it is up to each of us to decide which “source” to credit.

This ploy is used by ALL the feud yarn spinners. All of the recent “feud historians” notify their readers early on that the truth can never be known. In his “Author’s Note, King says: “Like every feud historian, I have occasionally had to rely on oral tradition…Parts of the feud remain shrouded in mystery and probably always will.”

Lisa Alther, another novelist who caught a wave in the wake of the Costner movie to ring the cash register with a “feud history,” wrote: “My version of the feud derives from these sources and others. It may be that some anecdotes I excluded actually happened; it may be that some I did include didn’t happen. In the end, it comes down to the judgment of each person.”

The history professor, Otis Rice, wrote: “Moreover, many of the details of events in the feud may never be known with certainty, for accounts, even by participants, were often so contradictory that there is no way of determining precisely where the truth ended and fabrication began.”

It is amazing to me that more intelligent readers do not wonder why writers who claim to be writing history begin their books by saying that there is no real history. Of course there is a method to this madness, because, once the reader is convinced that the truth can never be known, then any “truth” posited by the novelist masquerading as a historian becomes as much a truth as anyone else’s truth.

The obvious purpose of the three end notes above is to convince readers that there is no choice but to decide which of the prior yarn-spinners we should believe. King never mentions the fact that the details of the Elias Hatfield case are available for anyone who will pay twenty-five cents a page for the four-hundred-page file, and read it. He never mentions that case!

King tells us in note 11 that Governor Atkinson was the man who convinced Elias Hatfield to surrender. That, too, is false. But he leaves it as if there is no way to know who facilitated the surrender. Of course he could direct the reader to the case record, where the man who got Elias to surrender actually testified, but if he even mentioned the case record, his entire yarn is dead.

Here is the testimony of Dr. Bartram, who arranged the surrender of Elias Hatfield:

Q: I will ask you what you did towards arranging the surrender?

A: I told Bob Hatfield that I thought it would be the best thing for him to do, to surrender, and he asked me to write to the Governor, and I did so, and he asked me to wire, and I did so. And the Governor asked me to arrange the time of meeting, and I saw Bob Hatfield and arranged with him, and he came at the time when the meeting occurred.

Q: Where did it occur?

A: At Wharncliffe.

Elias Hatfield surrendered TO Governor Atkinson, after the doctor had convinced him that it was the proper thing to do. The Governor actually came to Wharncliffe, and received the surrender of Elias in the saloon owned by Elias’s brother, Bob. Devil Anse, Cap and Bob Hatfield were also present in the saloon with the Governor when Elias surrendered.

King says that Elias Hatfield was a N&W security officer, on his way to Wharncliffe, and the call boy, Andy Chafin, saw Ellis and Hatfield square off with pistols. King says that Hatfield shot Ellis in the neck, with the bullet exiting the top of his head. He would never admit that there is a record of sworn testimony, unrebutted by the opposing side, that Elias was there to get ice for his saloon, and the call boy was actually Ed Guntner, and the two men had rifles and the bullet which killed Ellis never exited.

If I wrote of every yarn in Mr. King’s book that is refuted in detail by the record, the book would be longer than the 430 pages used to spin the yarn. But this series of posts gives the reader an idea of how feud history is “made.”.