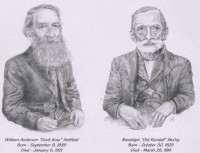

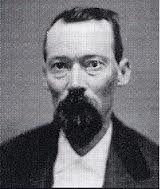

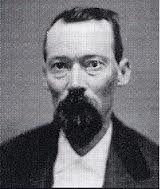

The two most misrepresented of all the feud characters are James Vance, whom we covered in an earlier post, and Perry A. Cline.

The treatment of Perry Cline by the feud writers is as atrocious as is that of Jim Vance. As in the case of Vance, the picture of Cline painted by the yarn-spinners is a mixture of ignorance and lies. The historical Perry Cline was far more different from the one the feud writers portray than Ronan Vibert is from the real Perry Cline.

There is a lot of Cline history that does not appear in the feud stories. Here is a small part of it.

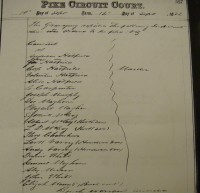

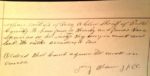

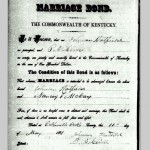

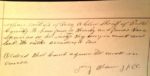

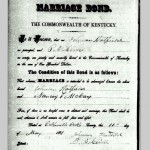

This photo is a Pike County Court document from December, 1874, showing Perry Cline becoming Sheriff of Pike County, at the age of 25. His bond was signed by the two wealthiest men in the county, O.C. Bowles and John Dils. Dils and Bowles were Republicans, and Cline was a Democrat. Dils was also foster father to Perry Cline.

Click the thumbnails to expand them.

I know it will shock people who know nothing but what they have read in the feud tales, but the third signer of Perry Cline’s bond was none other than his close friend, James Vance. The feud yarns tell us that Perry Cline thought that James Vance murdered Cline’s brother-in-law, Asa Harmon McCoy in 1865. This record shows that Perry Cline and James Vance were the closest of friends ten years later. Does any sentient human being think that Perry Cline had a man sign his sheriff’s bond whom he thought had murdered his sister’s husband? I don’t think so.

I know it will shock people who know nothing but what they have read in the feud tales, but the third signer of Perry Cline’s bond was none other than his close friend, James Vance. The feud yarns tell us that Perry Cline thought that James Vance murdered Cline’s brother-in-law, Asa Harmon McCoy in 1865. This record shows that Perry Cline and James Vance were the closest of friends ten years later. Does any sentient human being think that Perry Cline had a man sign his sheriff’s bond whom he thought had murdered his sister’s husband? I don’t think so.

Perry Cline then appointed James Vance as his first Deputy Sheriff.

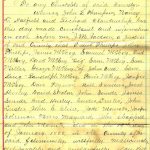

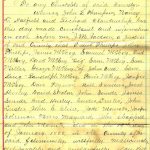

Perry Cline’s record for being the youngest man ever elected sheriff was broken a few months after Perry Cline’s death in 1892 when his son, John Sinclair Cline, was elected sheriff at the age of 23. The December, 1892 bond for John S “Sink” Cline, shown here, was signed by the same O/C. Bowles who signed his father’s bond. The first signature on Sink’s bond was his mother, Martha Adkins Cline.

The Kevin Costner movie showed Perry Cline chasing Roseanna McCoy for years. That is a slander of the man who, as the record shows, was devoted to his wife, Martha Adkins Cline. In 1875, Perry Cline sued a man for ten thousand dollars—a fortune in those days—for spreading the tale that he had slept with Cline’s wife. In 1877, Perry Cline sued several men for five thousand dollars because they made too much noise outside his home when he was away, disturbing his wife‘s sleep.

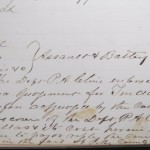

John “Sink” Cline was not only the youngest man ever elected to Pike County’s highest office, he was also the only man ever elected who was facing a murder charge at the time. This photo is the January, 1888 Logan County warrant for the men charged with the murder of Logan County Deputy, Bill Dempsey. John S. Cline is among the men charged.

One may wonder how Logan County identified 24 men from Pike County, even to such detail as saying that George McCoy was the George who lived on Johns Creek. The answer is at the top, where the three people who swore out the warrant are listed. One of them is Nancy L. Hatfield. Nancy was the daughter of Asa Harmon McCoy, married to Johnse Hatfield at the time, and living on Grapevine Creek where the murder happened. Nancy knew them all.

A few months after that warrant issued, the Pike County boys caught a BIG break. Nancy left Johnse and moved in with Frank Phillips on Peter Creek. Without Nancy as a witness, the charges against 18 of the 24 were not pursued further by Logan County, because they had no witness to identify them in court. Of course the charges remained–murder has no statute of limitations–but Logan had no witnesses against most of them. John S. Cline was one of the men against whom no witness other than Nancy was available to testify.

Perry Cline’s political power had two foundations. First, the richest man in the county, Colonel Dils, was his legal guardian. Second, and most important, Perry had virtually unanimous support on Peter Creek. Peter Creek, which was about 80% Republican, voted almost unanimously for the Democrat, Perry Cline.

My Dotson ancestors were Union sympathizers, Union soldiers in the Civil War, and the strongest Republicans on Peter Creek. My Great Grandfather, Ransom Dotson was one of only five Republicans who showed up to vote for U.S. Grant in 1868. In 1878, he named my grandfather after the Democrat sheriff. Squire James L. Dotson, long-time Republican justice of the peace and the richest of the Peter Creek Dotsons, gave a son the full name of the Democrat sheriff—Perry Cline Dotson. When I asked my Grandma Dotson, nee Hatfield, why Grandpa was named Perry after Perry Cline, she had a simple answer: “Perry Cline was a great man.”

Perry Cline is known to feud book readers as a sneaky shyster lawyer, lurking in the shadows. Some say that he was afraid of Devil Anse Hatfield. In fact, it might have been the other way around. Peter Creek had the reputation of being the ‘roughest’ part of Pike County during and for decades after the Civil War. Granny always said that Peter Creek was a good place to get yourself killed.

Perry Cline did not become the political force he was by being a sissy. At the time my grandfather was named for Perry Cline, Cline was facing the charge of Voluntary manslaughter. He had killed a man he was arresting, and the grand jury thought he had used excessive force and indicted the sheriff. Cline stood trial in 1878, and was acquitted.

Perry Cline was the only major character in the feud story who killed a man outside of war before 1880.

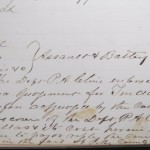

In 1878, while serving as Sheriff, Perry Cline and his wife were both charged with assault and battery. Perry pled guilty and the charge against Martha was dismissed.

After I read the book by Virgil Jones in 1952, I asked Uncle Ransom Hatfield, son of Preacher Anse, to whom I delivered the Williamson Daily News from 1952 to 1955, about Perry Cline. He said that Perry Cline was the most feared man in Pike County, even moreso than his foster brother Bad Frank Phillips.

Perry Cline was feared by all, including moonshiners. The Big Sandy News reported on May 31, 1888 that Jailer Cline burst into a warehouse where SEVEN moonshiners were tending their wares and arrested them all.

Uncle Ransom was right, and the feud liars who present him as a cowardly shyster are LIARS!

Uncle Ransom was right, and the feud liars who present him as a cowardly shyster are LIARS!

Ransom said that Perry stood trial for manslaughter while serving as High Sheriff, and was acquitted. He said that, on the way out of the courthouse after being cleared on the manslaughter charge, Perry “Beat Hell out of the main witness against him on the courthouse steps.” He said that Perry’s wife, Martha, helped him whup the man. I wondered if that was just a front porch tale, until I researched the feud story as a college student several years later.

Look at the two incidents reproduced above and you will see that Uncle Ransom was telling the truth. Cline was acquitted of manslaughter on March 15, 1878, and both he and his wife were charged with assault and battery on the 16th.

The feud yarns say that Perry Cline signed his Grapevine land over to Devil Anse because he was afraid of Devil Anse. Testimony by both sides in the Torpin case says that Cline sold that land to Devil Anse. In March, 1877, Perry Cline signed the deed transferring ownership of the Grapevine land. Land that is transferred by deed is NOT stolen

One year after that deed, the record proves that there was NO ill-will between Perry Cline and Anse Hatfield in 1878. Devil Anse lost a lawsuit to G.W. Taylor, and the court ordered the sale of 800 acres owned by Anse on Peter Creek to settle the judgment. That 800 acres, centered on Point Rock Hollow, was the subject of multiple court actions. One can learn a lot of our history by following that acreage through the courts over a half century.

During the Civil War, the Peter Creek Union Home Guards, under Bill Francis and Peter Cline, raided the farms of George (my 3g grandfather) and James Hatfield on Blackberry Creek. George had four sons serving in the Union army at the time–including James–but that made no difference to the Peter Creek raiders. They robbed everyone that could not defend their homes.

After the War, both George and James sued the raiders. George won his suit and collected. When James won his suit a year later, Peter Cline could not pay the judgment and 800 acres that Cline owned on Peter Creek was sold by the court to settle the judgment. James Hatfield bought the land at the courthouse door, and then immediately traded it to Devil Anse Hatfield.

That is the land that Perry Cline, as Sheriff, was ordered to sell in 1878, to pay the judgment against Devil Anse.

Now, we are in 1878, when all the feud stories say that Perry Cline hated Devil Anse because Devil Anse stole Cline’s land in 1877. If that were true, then surely Cline would have enjoyed very much selling Anse’s land at the courthouse door. But Cline did NOT sell the land, even though, as Sheriff, he was required by law to do so. Instead, he took his brother-in-law, Boney Adkins and a Peter Creek neighbor, Martin Smith, and went across the river to the Logan county home of his friend, Anse Hatfield.

By Cline’s own sworn testimony, we see that he arranged for Martin Smith to co-sign a note for Anse. Then Cline took the note, paid off the judgment, and allowed Devil Anse to keep the land.

Now that’s one heckuva favor to do for someone you hate, ain’t it?

How strong was the friendship between Perry Cline and Anse Hatfield in 1878? Well, that 800 acres that Perry helped Anse to keep when he was supposed to sell it at the courthouse door once belonged to Perry Cline’s brother, Peter Cline!

Then, three years later, Perry Cline’s niece married the son of Devil Anse. Not only did Cline bless the wedding, he signed the $100 bond guaranteeing that the wedding would take place. A hundred bucks was a lot of money in 1881.

Perry Cline and Anse Hatfield were enemies in 1887-8, but that is a whole ‘nother story. It had nothing to do with anything that happened in the 1860’s (the killing of Cline’s brother in law, A.H. McCoy) or in the 1870’s, or anything else connected to a “feud,”. The problems in 1887-8 sprang from what was going on with respect to the valuable coal lands owned by the Hatfields. And it was controlled by people much higher up than Perry Cline.

John Sinclair “Sink” Cline was left out of all the feud books until 2013. Dean King has a lot about John S. Cline in his book, but it is all just fiction, telling you nothing that is real about the man. I know folks are surprised by the affidavit from Nancy McCoy Hatfield, shown above, which listed Sink as one of the murderers of Deputy Dempsey. OTOH, no feud writer before me ever told folks that Sink Cline was elected High Sheriff of Pike County at the age of 23.

There were folks alive on Blackberry Creek when I was growing up who remembered Perry Cline. My Granny was one of them. There were many who remembered John S. Cline. they pronounced his nickname “Sank.” Until I was a college student and researched the records, I thought his name was John SAINT Cline. I mistook the Blackberry pronunciation of “Sink” as “Sank” for the word “Saint.”

I am dedicated to the real history of our ancestors, who have been slandered for a century and a quarter. They are all one-dimensional characters in the feud fables, but the actual record shows that they were complicated, multi-dimensional characters, who behaved as normal people of their time behaved.

Perry Cline was a low-down crooked politician to his enemies. To his friends, like my Great Grandfather, he was, as my Granny told me, “A great man.” I have tried in my books to show the complete Perry Cline. I endeavor to do the same for all our ancestors.