The West Virginia Encyclopedia is extremely damaging to the study of real history, simply because it has the State’s imprimatur upon it. We saw the lack of concern for the historical record in my blog post a few months ago on the Encyclopedia’s handling of the Abner Vance story. http://hatfield-mccoytruth.com/2014/11/24/the-west-virginia-encyclopedia-on-the-feud-tilting-at-a-big-windmill/

In response to an inquirer who offered to bring the documentary proof that the Encyclopedia’s article was in error, the editor said he didn’t need to see the evidence, because he liked the story and would leave it the way it was.

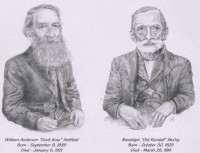

Surfing the net for “feud” stuff the other day, I again ran into the “Devil Anse had a guerrilla group that was known as The Logan Wildcats” claim. Of course anyone who has studied the real history knows that the Logan Wildcats were Company D of the 36th Virginia Infantry, and they never operated within a hundred miles of Tug River. Devil Anse was never a member of the Logan Wildcats, much less their leader. The writer, like most recent writers making that spurious claim, cited the West Virginia Encyclopedia.

What makes it doubly sad is that the writer undoubtedly thought he/she was writing history, simply because it came from a website with the name “West Virginia Encyclopedia” at the top of the page. Anyone who took the trouble to check the writer’s sources would have been doubly reassured when he looked at the Encyclopedia’s article, because it has this at the bottom:

Cite This Article: Spence, Robert Y. “Logan Wildcats.” e-WV: The West Virginia Encyclopedia. 07 October 2010. Web. 10 March 2015.

The West Virginia Encyclopedia says that Devil Anse was the leader of the Logan Wildcats, and its source was the historian, Robert Spence; therefore, who can blame a researcher with no prior knowledge for accepting it as gospel? The blame lies with the Encyclopedia, not with the honest researcher who accepts what the Encyclopedia says as history, and here is why:

Robert Spence was the co-author of a book with Coleman Hatfield called “The Tale of the Devil.” That book, first published in 2003, has some 25 pages about Devil Anse and the Civil War. About half of it concerns the Logan Wildcats, which Spence and Hatfield never say was the name of Devil Anse’s guerrilla band. All of their writing about Anse and the Logan Wildcats refers to the real Logan Wildcats, Company D of the 36th Infantry, but the name of Anderson Hatfields never appears on a muster roll for the Logan Wildcats.

There is not a single sentence in the long chapter which says that Devil Anse’s raiders during the last part of the war were known as the Logan Wildcats. Surely if it had been true, the authors would not have let such a colorful name slip by, but they never once said that Anse’s home guard was known as the Logan Wildcats. They confined the moniker to its real application throughout.

Of course this brings us to the question of why did Spence write in the Encyclopedia that Anse’s band of Tug River raiders was known as the Logan Wildcats, when he did not say it in The Tale of the Devil.

The Encyclopedia tells us to cite the article as being by Robert Spence, with a date of October 7, 2010. I can hear my readers shouting at me: “That settles it, Dotson. Now shut your mouth!”

“Not so fast,” I respond. “Look at the date.”

Robert Spence died in 2005, but the Encyclopedia wants us to ascribe something to him that was written in 2010. Something smells about this. I am no expert on West Virginia’s Civil War units, but from what I know, the first two paragraphs of that article are correct, and were probably written by Robert Spence.

The last paragraph about Logan Wildcats along the Tug is pure Hatfield-McCoy hokum, and was likely added after Spence died—it is so dated—dishonestly retaining the claim that it was all written by Robert Spence. The editor of the Encyclopedia is obviously careful to edit his Encyclopedia to keep it up-to-date with the latest tale in the latest feud book put out by the feud industry. As he proved when confronted about Abner Vance, he does not give a hoot in hell for our real history.

Shame, shame, Mr. Editor. You are destroying the credibility of something that the taxpayers of West Virginia are paying for. You have most likely not heard the last of it.

PS: At my age, most of my readers will outlive me by at least a decade or so. If someone tells you that I wrote something five years after I died, please do NOT believe it!