- [I’ve come to believe that manufacturing a feud tale is a bit like making moonshine. For moonshine, you can take (according to at least one recipe) 8 lbs of crushed corn, 1.5 lbs of malted barley, 5 gallons of water and 1 package of bread yeast and, through a carefully controlled process of mixing, fermenting and distilling, output yourself a small batch of good corn whiskey. Gold from lead, so to speak. Our feud tales, from the earliest ones on record to the latest ones published and promoted by the largest of industrial conglomerates, rely on a similar (al)chemical process. You take 2 parts old newspaper stories, 1 part wild tale passed down through a local family, 3 parts unsourced quotes from previously-written books, and 2 parts self-invented detail, mix it carefully together on the page (with no regard whatsoever for the truth) and, viola!, feud tale. At the very least, your every detail, even the invented ones, become potential ingredients for the next feud book cooked up by the publishing industry and at best you find yourself with a bestseller and possibly even, why the hell not?, a TV show! Here’s the thing, though. These concoctions are not good for your brain. They cloud your judgement. They make you see things that aren’t true and, if examined for half a second in the cold light of sobriety, are clearly ridiculous. So, to keep my little analogy going, Thomas is a feud tale revenuer, stalking the backwoods of feud research and feud books to find the source of all this bad hooch, which, with careful blows of the axe, he smashes and leaves in ruins. Seriously, all of these feud books, with the exception of Altina Waller’s book and Thomas Dotson’s books, should come with a warning label: Warning! Feud Book. Claims to historical accuracy lack foundation and may cause blurred vision and permanent memory loss. Read at your own risk. – RYAN HARDESTY]

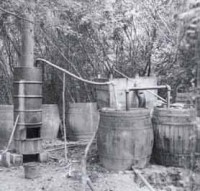

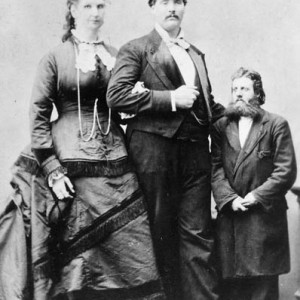

- This forlorn scene might represent Devil Anse Hatfield’s moonshine still in late 1880. According to Dean King, Anse’s lucrative “likker” trade was in the doldrums due to a labor shortage. King writes that “Devil Anse’s sons were not keen on the hard work required,”[i] so the old mountaineer had to look elsewhere. Even though Devil Anse had dozens of close relatives—brothers, cousins, nephews—living close by, he could find no one willing to do the work associated with tending a still.

How this could be so when Anse had no problem finding forty relatives and neighbors to do the back-breaking labor of timbering in the hills is not divulged. We must accept it as true, however, because the Boston Globe assures us that Mr. King is a historian.

At a time when, according to King, Anse Hatfield was involved in a furious blood feud with the McCoys, he solved his labor shortage at the still in a most surprising manner; he hired Jim McCoy, the eldest son Ran’l McCoy!

King assures us that a moonshining enterprise was “an endeavor that required absolute faith among participants,” but he expects us to believe that Devil Anse and Ran’l McCoy’s eldest son were in the moonshine business together in 1880.

That was two years after the hog trial, which, according to King, featured dozens of armed Hatfields and McCoys, turning out to support their respective sides. It was also the same year that Sam and Paris McCoy killed Bill Staton, Johnse and Roseanna had their fling and Devil Anse took Johnse from Jim’s brothers at gunpoint. It was within a few weeks of the time when, according to King, more than a hundred armed McCoys invaded Anse’s county seat of Logan.

King does not tell us whether Jim came to work at the still the morning after Devil Anse stripped his brothers of their prisoner. Maybe Jim was actually living in the home of Devil Anse at the time, in order to avoid the commute of two hours every morning and evening by horseback from Pond Creek to Grapevine. King doesn’t say, so we will just have to guess.

The very idea that anyone — much less someone as intelligent and cautious as Devil Anse Hatfield — would allow a non-kinsman out-of-state outsider to even look at his still is preposterous. From the day that Lincoln signed the law in 1862, making the distilling of untaxed liquor a federal offense, until today, no operator of such a still would ever do such a thing. King repeats at least three more times the ludicrous claim that Devil Anse, a member of one of the largest families in the entire Valley, had such a shortage of willing workers among his kin that he had to employ an out-of-state McCoy at his still.

Any reader gullible enough to swallow this yarn will probably believe the dozens of even taller tales coming later in this “True Story” of the Hatfield and McCoy feud.

[i] King, Dean, The Feud, 67